Mobile Naval Air Base No. IX

Assembly and commissioning in the UK

Personnel and equipment for Mobile Naval Air Base IXI began to assemble on June 1st 1945 at RNAS Middle Wallop, Hampshire. It was to assemble as the second Fighter Support MONAB, essentially no different from a standard MONAB which would support both fighters and torpedo bombers, its scale of issue excluded tools and spares for non-fighter aircraft types.

The unit was allocated the following components which were to cater for all fighter types in use by the RN in the Pacific theatre:

Mobile Maintenance unit (MM) No. 8 supporting Corsair Mk. II & IV, Seafire Mk. L.III & XV

Maintenance Servicing unit (MS) No. 15 supporting Hellcat Mk. II

Maintenance Servicing unit (MS) No. 16 supporting Firefly Mk.I ?I

Maintenance, Storage & Reserve (MSR) No. 10 supporting - believed to be Corsair Mk. II & IV, Firefly Mk. I,

Hellcat Mk. II, Seafire Mk. III & L.III

(it is believed that this unit did sail with, and was attached to MONAB IX)

Like the two units before it, MONAB IX storing was done under the new system for the handling of unit stores; instead of all stores being delivered to the formation base to be checked, repacked and labelled ready for despatch overseas, everything was consigned directly to the port of embarkation from the store depots saving unnecessary transport and handling of store cases. It is not known if a trial installation was undertaken by this unit. The transport and specialist vehicles for both MONAB IX and MSR 10 were despatched to Liverpool Docks on July 20th.

MONAB IXI Commissioned as an independent command bearing the ship's name HMS NABROCK on August 1st 1945, Captain J.S.C. Salter D.S.C, O.B.E, in command. Under normal circumstances a MONAB would sail three weeks after commissioning, but the surrender of Japan on August 15th caused the Admiralty to take stock of MONAB operations; as a result, the departure of MONAB IX and MSR 10 was delayed by one week. During this time many personnel were sent on short home leave beginning on VJ Day.

Despatch overseas

The personnel of MONAB IX & MSR 10 arrived at Prince's Dock, Liverpool by train and embarked in the Troopship DOMINION MONARCH, she sailed the following day for Sydney, Australia via the Suez Canal. The DOMINION MONARCH made a fast passage, calling only at Port Said on September 8th to enter the Canal, and at Port Suez, on exiting the canal on the 9th, she them proceeded directly to Sydney arriving there on September 27th. However, only a small percentage of the MONAB IX complement, an advance party, was disembarked, the remainder stayed onboard and the ship sailed the next day for New Zealand. She arrived at Wellington on the 30th to disembark her main passengers, Maori POW's, who had been taken prisoner on Crete and interned in Germany, with their escort of New Zealand nurses who accompanied them. She called at Christchurch on October 2nd to disembark further ex-POWs before sailing for Sydney, arriving there on October 4th. Details of the Sea Transport vessel carrying the unit’s stores and equipment are not known, however sailing records august this was the SS SAMALNESS (7,176 GRT) which sailed from Liverpool on September 22nd 1945 taking passage via the Suez Canal for Sydney, she was redirected to Singapore while on passage and arrived at Singapore on November 8th 1945.

The Troopship DOMINION MONARCH docked at Dalgety's wharf, Millers Point, Sydney, New South Wales c.early Oct 1945.

The remaining personnel of HMS NABROCK were to remain onboard the DOMINION MONARCH which docked at Dalgety's wharf, Millers Point. They were to spend the next two weeks with no duties to perform, only a skeleton watch was kept aboard ship, the rest of the personnel had leave to spend their time ashore.

The decision had been taken that the unit should be deployed in the same manner as MONAB VIII and would re-open the airfield at Sembawang on the Island of Singapore. The unit personnel had been divided into four groups for the move to Singapore; The personnel that had disembarked on September 27th had formed three advance parties which were to travel by RAF Dakota transport planes via Moratai, in the Dutch East Indies in three phases. The remaining group, comprising of the main body of the unit was to travel by sea; they were to leave the DOMINION MONARCH and embarked in the Australian Troopship LARGS BAY for passage, embarking on October 17th.

The LARGS BAY was a vintage trooper, having been in service during World War 1, and the years had not been kind to her. Her last voyage been had to transport former POWs from Singapore, home to Australia and the ship had not been checked for infestations before MONAB IX embarked; The members of the main party were plagued by vermin from the moment they embarked. This was so bad fumigation was ordered when she docked at Port Darwin on the 24th before resuming passage for Singapore on the 26th.

Commissioned at RNAS Sembawang, Singapore

Following the Japanese surrender in the former British colony of Singapore on September 4th (Operation TIDERACE) The Admiralty planned to take control of the airfield at Sembawang . An advance party, under the command of Captain H.A. Traill OBE., RN, (formerly commanding Officer of the escort carrier EMPRESS) arrived soon after to take control of the airfield and prepare it for reopening. They found about 90 Zero fighters on the airfield and some 700 Japanese officers and men. The station was honeycombed with tunnels and foxholes and in a state of considerable disorder. The Japanese had been working to establish a north/south runway, using British prisoners of war, and there were at least a dozen Public Works Department steam rollers abandoned on what came to be called the Jap runway.

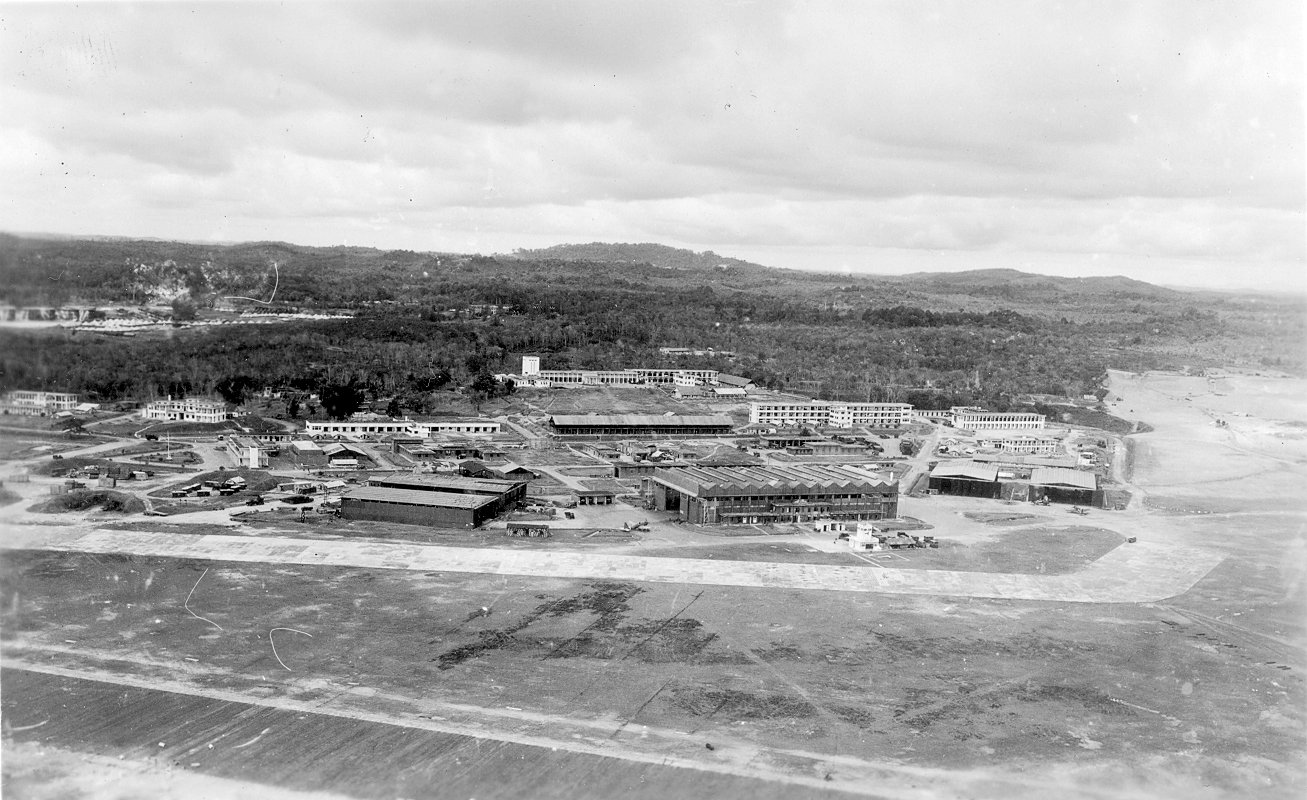

RNAS Sembawang C. early1946.

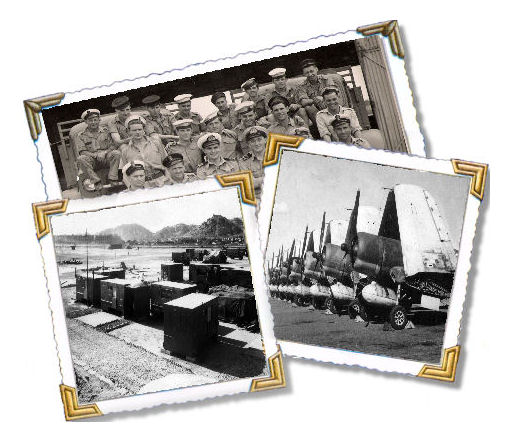

Work on restoring the station to working order was started immediately and Japanese prisoners of war were employed filling in foxholes and tunnels as well as the laying of a 1,400 x 50-yard pierced steel planking runway. Mobile Naval Air Base No. IX had been allocated to provide the necessary equipment and infrastructure to operate the station and initiate naval flying and aviation support facilities for the region. The advance party of MONAB IX commissioned Royal Naval Air Station Sembawang as HMS NABROCK, on October 5th 1945. At this time the airfield was still littered with derelict aircraft and other debris left by the Japanese and clean up and repair work was still ongoing. The first aircraft arrived on the station on October 8th, these were the (3?) Sea Otters of 1700 squadron 'C' flight which had flown from RNAS Katukurunda in Ceylon for a brief detachment; they returned to Katukurunda on the 20th. The main body of personnel onboard the LARGS BAY docked in Singapore on November 1st, exactly 9 weeks to the day since the DOMINION MONARCH had left Liverpool.

One big problem that faced the men of HMS NABROCK was they were unarmed: their weapons, as well as their equipment was still at sea and they found themselves guarding large numbers of Japanese prisoners who were employed as labour on the airfield. The weapons in the Japanese armoury were found to be sabotaged, the firing pins had been broken, but they were still issued to RN sentries guarding the work parties, there was no running water and the sabotaged sanitation system was still not repaired. .

Once the unit’s equipment and stores arrived, sometime in late November, work commenced assembling crated American aircraft, many of which were Hellcats. Once assembled these new aircraft were towed by road to the nearby dockyard and embarked in aircraft carriers to be ferried out to sea and dumped overboard. This strange practice was done to comply with the terms of the Lend-Lease agreement with the United States, under which these machines were supplied. Once the war was over Britain was required to return any surviving equipment or payment was to be made for them. The Americans did not want them back as there was now a huge surplus of warplanes and Britain could not afford to pay for then, so destroying them was the solution employed. It is assumed that MSR 10 undertook this aircraft erection work since MONAB IX was not outfitted for the task.

Paying Off

On December 15th 1945 HMS NABROCK was paid off at RNAS Sembawang, the station re-commissioning the same day as HMS SIMBANG. Effectively the MONAB ceased to exist, however the ship's company remained unchanged and work on erecting airframes for disposal continued. The Sea otters of 1700 squadron 'C' flight arrived back on the station on this date for a second period of detached operations.

A reserve MONAB The now decommissioned MONAB IX was to be retained at Sembawang as an enhanced reserve MONAB, its name and number being deleted; however much of the specialist equipment, such as the air radio and radar workshops remained in use for several years until purpose-built facilities were established. The bulk of the MONAB equipment was held in storage on a care & maintenance basis for reactivation should it be required. Its existing components were supplemented by extra equipment and vehicles recovered from the recently paid off units in Australia. It is believed that this reserve unit was maintained in storage at Sembawang until at least the mid nineteen fifties.

HMS 'NABROCK'

Function

Fighter support MONAB providing support for disembarked front line Squadrons.

Aviation support Components

Mobile Maintenance (MM) 8

Maintenance Servicing (MS) 15 & 16

Maintenance, Storage & Resave (MSR) 10

Aircraft type supported

Corsair Mk. II & IV

Firefly Mk. FR.

Hellcat Mk. I & II

Seafire Mk. III, L.III & XV

Commanding Officers

Captain J.S.C. Salter DSC, OBE 01 August 1945 to 15 December 1945

Related items

R.N.A.S. Sembawang History of the airfield and other information - part of the Fleet Air Arm Bases web site

Reminiscences

Memories of those who served with MONAB IX

Leading

Air Mechanic (Engines) Douglas 'Shorty' Heath

Sergeant

Bill Rees RAF

Stores

Assistant, P/MX736065 Jim Davey

Comments (3)

Do you have other photographs of MONAB 9, if not, I do.

Hi Tony, I have a copy of the photo. If you would like to contact me I am more than happy to discuss this further.

Are there any existing photographs of the NAB ROCK as my father served on it and in on the crew picture taken August 1st 1945