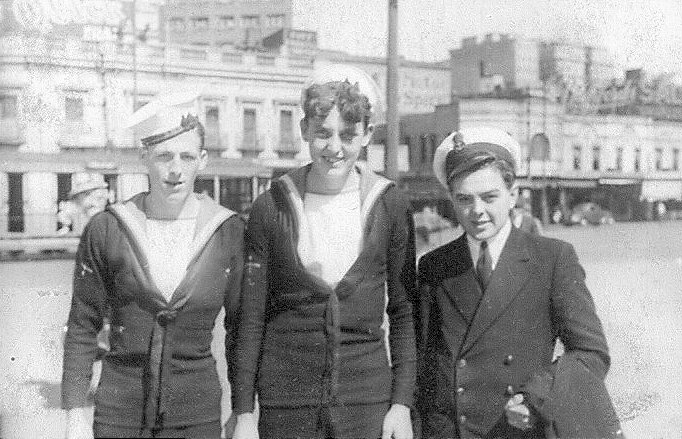

Air Fitter (Engines) Douglas Hooper (Center) and two colleagues ashore in Sydney

RNAS Bankstown looking to the Southeast, the aircraft park can be seen in the distance.

A closer view of the aircraft park at RNAS Bankstown

The wartime reminiscences of Lieutenant Gordon Pursall R.N.V.R.

The wartime reminiscences of Aircraft Artificer 4th Class (Electrical) Laurence Russell

The wartime reminiscences of Sub-Lieutenant Michael Price R.N.V.R.

Early days

I was born and lived in Nottingham and was 13 years old when the war started. This marked the end of my schooling as there was a restriction placed on the number of children who could assemble in any place, for fear of a bombing raid. Before I started work I spent 2 years in the Air Training Corps and visited several RAF stations and watched Lancaster bombers take off for raids over Germany. I quickly made up my mind that I wanted to be in the Fleet Air Arm as soon as I was able to.

In May 1943 when I was 17, I volunteered for the Royal Navy and was immediately sent to HMS ROYAL ARTHUR which, in peace time, was Butlin's holiday camp, near Skegness in Lincolnshire. I was kitted out with a uniform, hammock etc and despatched to HMS GOSLING, near Warrington, one of 4 units, to do basic square bashing and generally to learn the dos and don'ts of naval discipline. Unfortunately, my overall training took longer than most, as I had an unexpected serious medical condition that required surgery, which delayed the completion of my training.

I then went to RAF Hednesford to undergo the training that I would need in the Fleet Air Arm. I undertook 18 weeks of training as an engine mechanic. Following that, I spent about 12 months at Royal Naval Air Station Yeovilton. Whilst there, the situation changed rapidly and, in addition to the technical training we undertook, we were all trained to use a bayonet, throw a grenade and to fire both a Lewis machine gun and a Sten automatic machine gun.

Joining MONAB II and off to Australia

We were then sent on 10 days overseas leave. Where to? This was top secret - nobody knew! Following that, I returned home to Nottingham for a short stay with my family before I boarded the train for Portsmouth at Nottingham's Victoria Station, where my dad, along with my tearful mum and sister, waved me off.

The train was packed for the journey to the Portsmouth camp, where we watched a film about a new aircraft - the Firefly. We were only there one night and were subjected to a German bombing raid - the bombs dropped so close that our billet (along with its drowsy occupants) was moved off its foundations! The next day we boarded another train...destination unknown. After a long journey in the blackout, we got off the train at Liverpool and got onto a bus that took us to the docks. The board outside the docks which read 'Mersey Docks and Harbour Board' raised a laugh from all on the bus, as some wag had written 'and little lambs eat ivy' underneath - a line taken from a very popular nonsense song at the time called 'Mairzy Doats'.

We boarded a ship called the ATHLONE CASTLE and sailed well before dawn, as previously, no-one knew where we were heading. When the ship left Liverpool, it headed north into the Irish Sea and then West along the north coast of Ireland. The ship stopped there for several hours whilst a convoy assembled. It was a large convoy and was escorted by destroyers and corvettes which stayed with us for about 12 days into the journey, then they left us to head north to North America, whilst we continued on a heading for the Panama Canal, with occasional support from US Catalina flying boats.

I must say at this point that from leaving Liverpool and arriving at the Panama Canal, where we were allowed 2 hours shore leave, we had no idea whatsoever where we were or where our final destination was to be, but we pieced the journey together either as it happened or by later reflection on the journey. We were permitted the shore leave at the Panama Canal as there was a queue to sail through the canal. The canal was fresh water and, as the ship had been drawing water for washing and showering direct from the sea, immediately the ship entered the canal, the crew and passengers made a dash for the baths and showers, as soap would not lather in sea water - having fresh water was a real luxury!

A day after leaving the canal and entering the Pacific, one of the ship's engines broke down, which left us drifting for a couple of days. Everyone onboard had to wear life jackets day and night. After the repair we seemed to be moving faster than ever. We still didn't know exactly where we were going for what so often, seemed like forever. However, one morning I woke early and realised that the ship was no longer moving, so I slipped out of my hammock and went up on deck. I just couldn't take in what I was looking at - it was Sydney Harbour Bridge. I recognised it only because I had been shown a picture of the bridge during a geography lesson at school a few years earlier. I reflected on the words of my geography teacher who had told the class that we would never have the opportunity to see it in our lifetime!

We eventually docked and quickly disembarked onto the double-decker buses that were waiting for us. We were driven through the centre of Sydney and out into the country. All the way along our route people in the streets were waving to us.

Life at Bankstown

Before long. we got to our destination, which was at Bankstown airfield - MONAB II, also known as HMS NABBERLEY. On arriving, we were shown to our billets and told to get some sleep as we were due to start work that night on the night shift, assembling and ground testing British and American aircraft, which were then flight tested by brave pilots from the Fleet Air Arm and the RAAF. I lost count of how many aircraft were built and tested there, but I recall that there was only one flying fatality, that of an RAAF pilot who flew a Firefly which crashed into the sea and was never recovered.

At the start, things didn't work too well. As the aircraft went out on the airfield, daily inspections of all the aircraft were introduced, where snags were identified and these had to be put right before any flights were authorised. Slowly things became more orderly. As previously mentioned, one aircraft that we worked on was the Firefly, which we had not had the benefit of working on before and had only seen once, on film, on the overnight trip to Portsmouth that I mentioned earlier. It's Griffon engine was much more powerful than the more familiar Merlin engine, but we all took it in our stride. I spent most of my time at MONAB II actually on the airfield carrying out the final daily inspections and making the final preparations readying the aircraft for flight. Our routine continued until the sudden end to the war was brought about by the bombing of Japanese cities with atom bombs.

My stay with NABBERLEY was a mixture of very hard work, but also lots of fun and happiness. I'm sorry to say that I can now only recall one name from the crew of NABBERLEY, he was Arthur Bailey and is in the photographs I am sending. He originally came from Sheffield, but chose not to return to the UK and married a local girl.

HMS NABBERLEY, like all shore-based naval establishments, was run as a 'ship' and all ratings belonged to either the 'Starboard' or 'Port' Watch. Only members of one watch were allowed 'ashore' at a time. We had a daily rum ration and a NAAFI canteen. The big lecture room doubled as a cinema. As I recall, the NAAFI was well supplied with the local brews and it was cheaper to have a drink there, rather than pay travel expenses out of our pay, (which was around £2.10 shillings (Australian currency) per fortnight), to either Sydney or Bankstown, where minis and schooners were served, whilst the NAAFI managed half pints and pints, which were bigger! We had more duty-free cigarettes than we needed, we also had the naval tobacco allowance of 8oz of cigarette tobacco (roll your own) or pipe tobacco per month. I recall that a local trader was allowed to bring in a van full of meat and fruit pies for our mid-morning break on workdays. The ratings were marched to work and marched to the galley for meals, but we were left to our own skills when we were working on the aircraft!

Whilst I'm reminiscing, I must pass on some of my thoughts about the air station - sorry, I should say 'the ship'! The accommodation for 'other ranks' was brand new corrugated huts, probably about 30 feet long and about 14 feet wide, they had good wooden floors, well above the ground. I was accommodated in hut no. 205. The toilets were housed in a similar building, the toilet 'bowls' were holes in wooden panels, which were over a trough of flowing water and were in a row about 3 feet apart, with no seat and no partitions, so we just sat there talking to each other! The showers were in the same type of building. Each shower was about 3 feet apart, again no partitions! We all knew each other quite well! We almost always slept under mosquito nets and, on waking each morning, we had to shake out our boots to get rid of some quite big spiders and on one occasion, a very small snake!. Each weekend every hut was inspected for cleanliness by the ship's captain and the 'star' hut earned the occupants a days leave. Another prize, if you were lucky, was to be taken for a flight in a high wing mono plane out over the sea and back.

A Royal vest and unexpected detached duties

We had a surprise royal visitor, the Duke of Gloucester, whilst I was at Bankstown. We had to turn out in full battle gear, with white knee length gaiters and belt and a rifle with a brightly polished bayonet. We had spent all of the previous day polishing bayonets, whitening our belts and blacking our boots! The Duke was dressed in full army uniform, probably rank of General. His khaki uniform was adorned with scarlet flashes on the lapels, cuffs and trousers. I was sure he was wearing make-up, as his cheeks were the same colour as the scarlet on his uniform!

On one occasion in late 1945 or early 1946, an Avenger aircraft had to make a forced landing at Mascot airport in Sydney, due to a problem. I was sent along with an electrician to attend to it. Whilst we were there, one of the first civil flights from the UK landed. It was a civil version of the Lancaster bomber, called the Lancastrian. I was told that the flight had taken over 3 days!

On another occasion I, along with another rating, was sent to an aircraft carrier, HMS INDOMITABLE, which was docked in Sydney. There was a fault on one of the aircraft onboard, which we had to fix. Whilst we were onboard, the carrier set sail, those in command apparently not aware that we were still there working. Unable to turn back, my workmate and I had 3 weeks unscheduled 'leave' whilst HMS INDOMITABLE sailed to the Solomon Islands, where we were put ashore to wait for another ship heading for Sydney to take us on the return journey!

The people of Sydney were very friendly and a building was erected in the city and called the 'British Centre', where we could go and have a meal and a drink. We could also get advice about leave accommodation. Many local people, who were delighted to have us in their country, opened their homes up to us to stay and they arranged for me to have a weeks' leave in Katoomba in the blue mountains, which reminded me of Devon in the UK.

Coming home

Over the months after the war came to end, MONAB II was decommissioned and on or around 2 March 1946, a call came over the tannoy to all ratings to pack up their belongings and report ready for repatriation! 1,400 of us boarded the SS GEORGETOWN VICTORY, a US victory ship, to be transported home to the UK. Our journey home was via the ports Freemantle, Colombo in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Aden, where we took on supplies and fuel. Our next stop was the UK. The last leg of our journey was via the Red Sea, the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean and then into the Atlantic and the Bay of Biscay, heading for the Irish Sea and onto Glasgow. As we got close to the UK, I recall us all listening to the FA cup final on board the ship. It was on 27 April 1946, Charlton v Derby County. Derby won 4-1.

Shipwrecked!

Just before midnight, on 29 April 1946, as the GEORGETOWN VICTORY sailed north up the Irish Sea heading for Glasgow, the ship hit rocks and broke its back just off the coast of Ballyhornan, County Down, Northern Ireland. The shipwreck was close to the coast and some of those on board were taken to the shore by boat, but as the tide turned and started to go out, some of us were able to wade to the shore. Unbelievably, everyone survived, although I understand that a couple of those on board were injured and were kept in Belfast hospital.

We were all transported to RAF Bishops Court, an airfield which was on the coast close to the shipwreck. We only had what we stood up in and, as the disaster had happened just before midnight, the majority of us were in our underwear. Most of us lost everything. We were given breakfast at the airfield and allowed to go to the local Post Office to send a 5-word telegram to our families. Mine read 'Am safe in Ireland, Doug'. When my parents received it, it read 'Safe on an island, Dog'!

As an aside, I will mention here a quite incredible coincidence that occurred just over a year later. In1947, I met my future wife Eleanor, who was visiting Nottingham to see her sister, who had married an acquaintance of mine. Whilst telling Eleanor about my time in the Fleet Air Arm, I told her about the shipwreck off the Irish coast. To my amazement, she said 'I was there'. She was in the WAAF and at that time was stationed at RAF Bishops Court. She clearly recalled the morning that the sailors from the GEORGETOWN VICTORY sat on the grass in their underwear, after eating the camp's entire breakfast supplies!

We were given some basic clothing then transferred to Belfast for a crossing to Glasgow, where we were fed again and put on a train to Edinburgh. We were then taken north to an old Fleet Air Arm station where we were given some pay and a travel pass home for four days leave.

I boarded a train and eventually arrived at the Victoria Station Nottingham, where I had started the journey (in which I completed a total circumnavigation of the world), at midnight on 4th May 1946. The blackout was still in force at this time and the station and its surroundings were in complete darkness. There were no buses or taxis, so I set off on foot for my parents’ home, which was about 2 miles from the station, still wearing the same clothing that I had been issued with at Bishops Court.

When I arrived home, I found that my cousin Joan was to be married the next day. I had no clothes except those I stood up in, but my resourceful mother visited a neighbour across the street and asked to borrow her son's naval uniform - he was an old school friend of mine, my age and height and had been demobbed a few months earlier. My recollection is that in those days, you had to pay for your naval uniform and therefore, kept it when you left the service. I had lost mine when the ship was wrecked, so it was a godsend to me to be able to borrow his uniform and I was able to attend the family wedding looking respectable and was given a round of applause at the reception when Joan announced that I had just arrived back from Australia a few hour earlier, having been shipwrecked on the way home - a real embarrassment for a 20 year old!

De-mob

Once the 4 days leave was over, I took the long journey back to Scotland to a run-down old Fleet Air Arm base known as HMS WAXWING, near Townhill, Dunfermline. There we went through the official de-mob routine and were all told that should any further war problems occur anywhere in the world, we could be called up again.

We were given rail tickets back home via York, where we were to pick up our choice of civilian clothing. We were told that we then had 6 weeks de-mob leave followed by a further 6 weeks survivors leave, so I had to start looking for a job - and there were plenty of them!!

Douglas Hooper

© 1999-2025 The Royal Navy Research Archive All Rights Reserved Terms of use Powered byW3.CSS

At the end of June 1945, the Admiralty implemented a new system of classification for carrier air wings, adopting the American practice one carrier would embark a single Carrier Air Group (CAG) which would encompass all the ships squadrons.

Sturtivant, R & Balance, T. (1994) 'Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm’ list 899 squadron as conducting DLT on the Escort Carrier ARBITER on August 15th. It is possible that the usual three-day evolution was cancelled due to the announcement of the Japanese surrender on this date and was postponed for a month.

Gordon served with the radio section of Mobile Repair UNit No.1 (MR 1) at Nowra, he was a member of the local RN dance band, and possibly the last member of MONAB I to leave Nowra after it paid off. .

In March 1946 I joined 812 squadron, aboard HMS Vengeance, spending some time ditching American aircraft north of Australia. Eventually we sailed for Ceylon ( Sri Lanka ) landing at Trincomalee and setting up a radio section at Katakarunda. In the belief that we were exhausted we were sent to a rest camp at Kandy for a few weeks. We moved down to Colombo to pick up Vengeance and returned to Portsmouth via the Suez Canal . I was discharged in November 1946.

Comments (0)