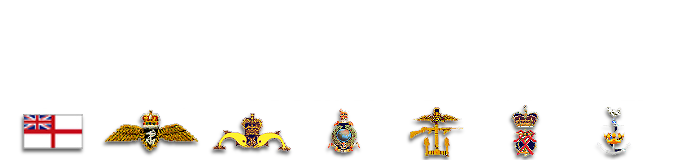

Able Seaman Alfred Walter Noel Langrish Z 123 Sussex Division RNVR & the Royal Naval Division

9 Killed in action

James G ALEXANDER, A.B. RNVR, Clyde Z 2267

Hubert R

BALDWIN, Ty/Lieutenant, RNVR

James F BELL, A.B. RNVR, Clyde Z 1575

Joseph

BELL, Private, RMLI, Clyde Z 2236

Arthur H BERG, A.B. RNVR, London Z 200

Victor COOMBS, A.B. RNVR, Bristol Z 325

Herbert

CUTTS, A.B. RNVR, KW 73

William

LINTOTT, Ty/Sub Lieutenant, RNVR

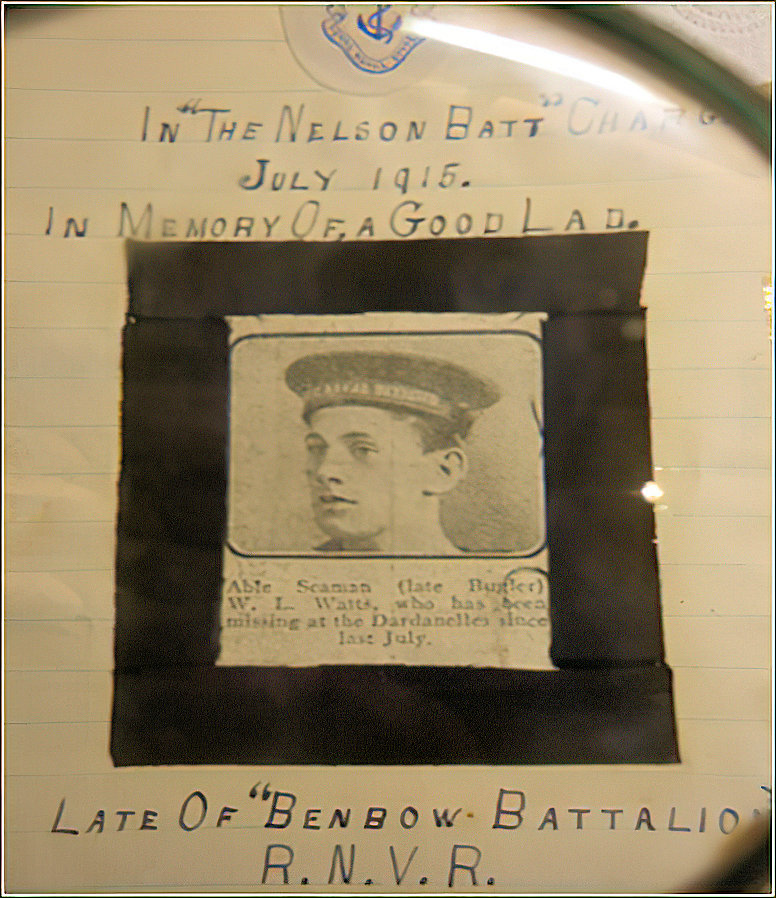

William L WATTS, A.B. RNVR, London Z 68 - (James Harts chum who was killed next to him)

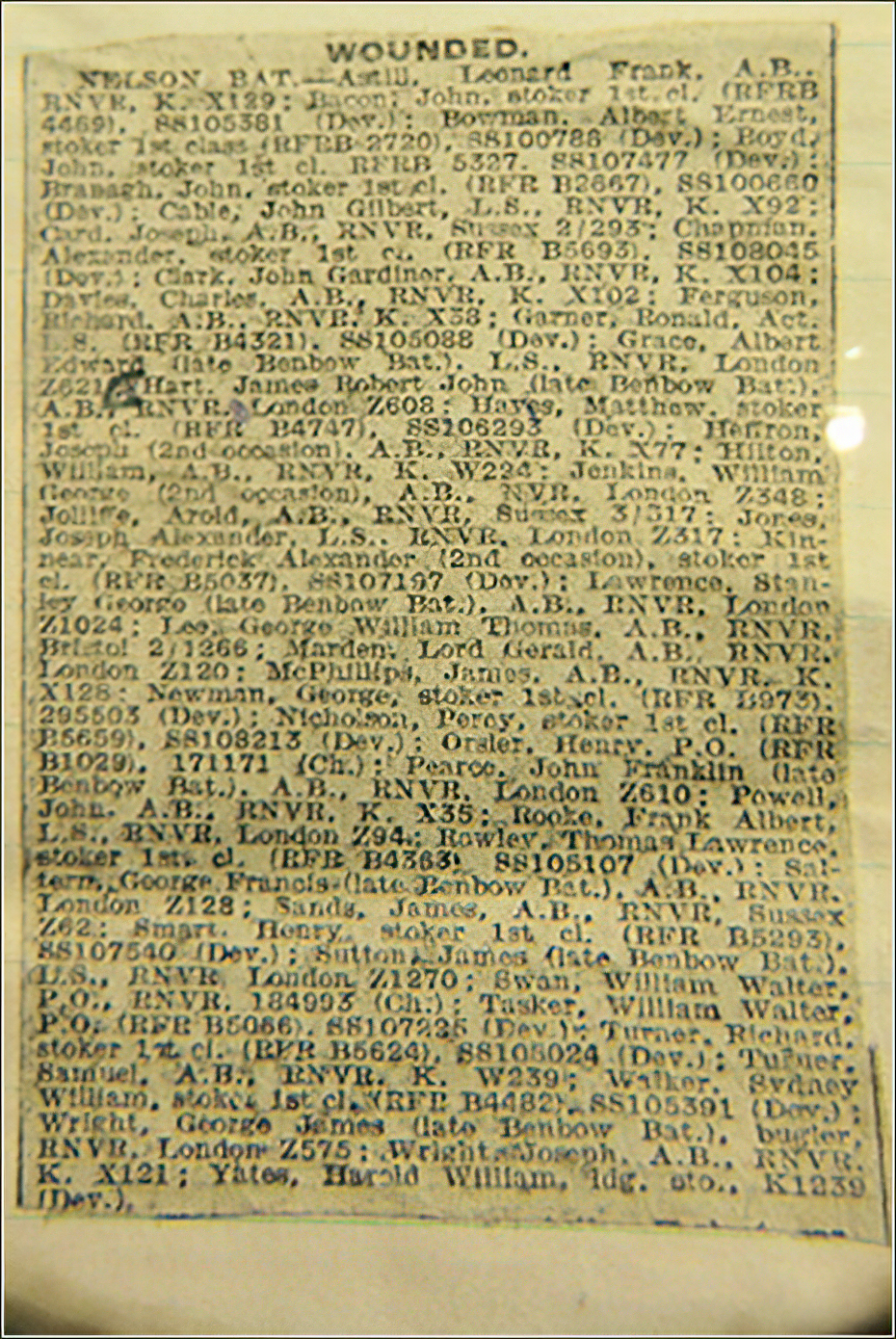

6 Wounded

A E GRACE, A.B., RNVR, London Z 261

S G

LAWRENCE, A.B. RNVR, London Z 261

J F

PEARCE, A.B. RNVR, London Z 610

G F

SALTERN, A.B. RNVR, London Z 128

J, SUTTON, A.B. RNVR, London Z 1270

G J

WRIGHT, A.B. RNVR, London Z 575

Killed in action

Thomas GRANT, A.B. RNVR, Clyde Z 1561 KIA June 6th 1915

Alexander GRAY, A.B. RNVR, Clyde Z 934, DOW in HMHS Grantully Castle June 9th 1915

George YORK, A.B. RNVR, Clyde Z 2066 KIA June 5rh 1915

Wounded

W DAVIDSON. A.B. RNVR, Clyde Z 1740

G JONES , A.B. RNVR, Tyneside Z 2240

G W

PARKER, A.B. RNVR, London Z 744

J WALLACE, A.B. RNVR, Clyde Z 3003 Age 20

J WALSH, A.B. RNVR, Tyneside Z 349

W WRIGHT, A.B. RNVR, Clyde Z 1396

A.B. = Able Seaman

[Sic] = Indication of written mistake quoted as is

The call of the country first came to me early in September, but owing to various reasons I did not respond, until a few weeks later. (Age 24 ~ RJH)

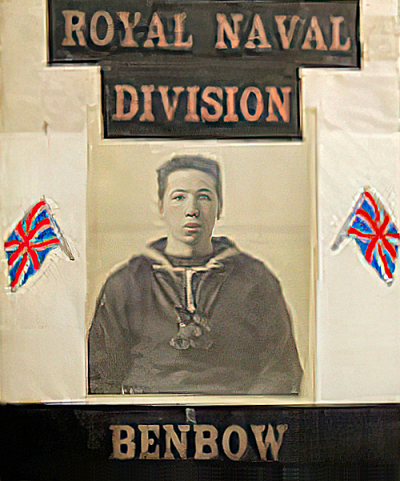

In October 1914, I made my way to the Naval Depot London, for the purpose of enlisting in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserves, as I had more desires for the navy than the army, although I had not any experience in either. Later on I found that my desires were to be very much crushed. There were also a few others who enlisted at the same time, two whom I made friends with, namely Harry Jackson and Jimmy Laxton and both proved very strong chums, during my whole experience in the service. We stayed at the Depot's for a week, doing drills, in the meantime, and then we were sent to the Crystal Palace, for a better training. On arriving there we found that it was being made into a large Naval Centre, for new recruits.

Nothing of very great interest happened at this place, only that we did plenty of squad drilling, and forming fours, which was enough to nearly send a fellow off his head. It was here that I made the acquaintance of another staunch chum namely Douglas Stafford.

The weeks passed here very quickly and we began to do all field training, after which we were told we would be required for land service. This was my great disappointment and it was also to [sic] many more, I might say that I began to learn the meaning of Red Tape, which was very prevalent. We next heard that we were to be moved to a place called Blandford, in the county of Dorset, and was told off, with a party to go on an advance guard. (Told off, a Naval term for orders ~RJH)

Off to Blandford: It was on a Friday in February 1915, when the day came for our departure into world's unknown, and we left the Palace at 9.20 a.m. for Victoria. After changing into different trains we landed safely at Waterloo. With just a beef sandwich and nothing to drink, we started on our long journey. We stopped at some of the stations, and in time reached Salisbury, half the journey only, and we all felt as dry as the bone, but the only water we could see was the flood, which was washing down the hill in torrents.

After a few minutes shunting we moved on again, but we did not go far before we had to change for another line. Then we had another ride for about an hour, and arrived at a little village on the map called Blandford. With only the job of getting out our luggage, and putting it in a steam wagon, we started on our never to be forgotten walk to the camp, a distance of 5 miles. We jogged along in mud, water, over our ankles, and in some places the water rushed down the roads, the watercourse not being large enough to hold it. We were getting near our destination when they called for a halt, as we had been coming along at a rate, and they told us that the camp was about 2 miles away. All that we craved for was a drink, but it seemed useless to hope for one. After a few minutes rest we started again, and arrived at our destination, with parched lips, and pounced on the first tap we saw.

The first thing we did was to draw a nice big blanket each, and then we went to tea, which consisted of bully beef, and pickled walnuts, but we greatly enjoyed it. After tea we made tracks for our sleeping huts, and after diving about in the mud, we arrived there safely. Never in my life have I seen so much mud, but as there was not any alternative, we had to wade through the lot.

My first visit was to the canteen, and as it was a large plain that we were situated on, in the dark it took some time to find. Each Battalion had its own canteen, and the first I walked into was the Bur canteen, of the Hawke Battalion. Taking our departure from here we went in another hunt for the Y.M.C.A. and after being smothered in mud all over, found the much desired place. With just refreshment we returned to our sleeping quarters, but to try and sleep was useless.

About 11-30 in the night my next bed chum asked me to pull a tooth out for him, but after tugging at it for about half an hour, I had to give up. Try and imagine if you can a lamp, and on the ground my chum, while I was trying to pull out his tooth, to relieve his pain, all without success. Thus ended our first day at Blandford.

Saturday, February 20th 1915

After a few hours sleep I awoke, feeling very sore in the back from lying on a board nine foot long. Went to breakfast had salmon, not any bread, or butter. Our first duties were to make a pathway from the officer's quarters, and after several slips in the quagmire, we succeeded in making a good path. Dinner time arrived, but we did not get enough to fill us, so away to the canteen we had to go. There was not much done in the afternoon, but in the evening we went to Blandford Town, and never again for it was bad enough to have to do it, apart for pleasure. This ended another day.

Sunday, February 21st 1915

Sunday morning, I awoke, feeling much the same as the morning previously, from the hard lying. Prepared for breakfast, which consisted of bully beef. After this very small feast we lined up for parade, and then received orders to start making footpaths. This I can assure you was above a joke, and we all complained, but it was no use, it had to be done, Sunday or not.

We had no knives or forks, so we had to make the best use of our fingers, and as we had Irish stew for our dinner, we had to put the plates to our mouths, and had to drink it. After dinner we had to fall in again to do some more work, but after a time dismissed ourselves, and so the day wore on. Sunday night was rather a lively time, as we nearly got flooded out, and had to shift our beds, at about 2.30 in the morning.

Monday, February 23rd [sic] 1915 (22nd ~ RJH)

Monday morning arrived with plenty of work in store for all, but we had a very amusing time unloading straw from carts. The meals never differed, and at dinner, complained to the officers. In the afternoon got tea room ready, for the rest of Company, and then got our straw beds at last, which reminded me very much of the days I spent with Friends Lads Camp. The Company arrived at last, and they looked like us, half dead. We had plenty of food this tea time.

Tuesday February 23rd 1915

We had plenty to do this day, and as we were now getting plenty of good food, we did it with good heart. In the morning worked on Officers quarters lying turf's, [sic/laying] and boards for footpaths. In afternoon, rehearsal of review, and march-past, for the King and Winston Churchill, this takes place Thursday. Just getting used to our surroundings.

Wednesday February 24th 1915

Road and path making until dinner time. Food is getting much better. Rehearsed, march past for the King, (on Thursday) in the afternoon, finished up with bread and butter for tea.

Thursday February 25th 1915

My turn to cook, and was sorry to miss the Review by the King. Dinner was the finest we had since our arrival in Blandford (that we had today). In the afternoon went on with path making in front of the Officers quarters, now getting settled to conditions, and surroundings. Canteen for our own Battalion opened to day. To give an idea of the camp, it is situated on the top of a hill, with some higher hills in the background, which set the camp off very nicely. The hills and the pure country extend for miles round.

The camp consists of the following Battalions ~ Hawke, Anson, Nelson, Benbow, Drake, Howe, Hood, Collingwood, and several Battalions of Royal Marine Light Infantry, not counting a vast army of transports. All these Batt's, [sic/Batts] are named after great admirals, and in all told, it is a camp of over 20,000 men, and to see them with, pith helmets on, and fixed bayonets, shinning in the sun, was a scene I shall never forget, as they went to be reviewed by the King. Several of these Battalions leave the camp on Saturday (27th Feb ~ Deal, Nelson, and Drake left via Avonmouth, ~ RJH)

Friday February 26th 1915

Nothing unusual happened to day only that I had to get free from all duties in the afternoon owing to pains in the little Mary, (stomach ache? ~ RJH) but after a few hours rest I was all right again. This being the end of the first week at Blandford , an experience I have never had before. I shall certainly try, and dodge an advance guard job for the Battalion, when we move on again. There is no amusement whatever to pass away the time and the only place to go is the canteen, as the Y.M.C.A. (Type of club ~ RJH) is so far off. So life in this camp is very dull, and the only thing for the Chaps to do, is have a singsong in the wooden hut.

We have all found out that we have left a good home, in leaving the Crystal Palace, where everything was so handy to get, and plenty of things to occupy ones [sic] time. Still I suppose this comes under the hardening process. After things had got settled and we had just about got used to the place, they began to put us through it, drilling, long route marches, day and night operations, in the field, and every thing in the soldier's line. But still we stuck it, and did very well, and after about three months training, we were told we should soon be moving off to the front, we were not told where, so we had to wait and see. At last the day came for our departure, to foreign lands unknown, for active service.

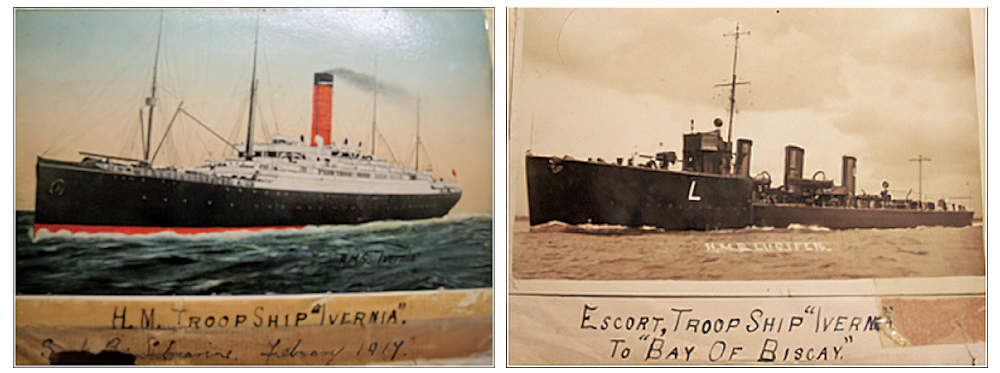

It was a glorious day in the first week of May, when we said farewell, to the folks of Blandford. People had come from miles around, to see us leave and wish us good luck. Mothers, wives, and sweethearts all saying goodbye to their loved ones, and it gave one such a feeling, that we were glad to get away from that scene of farewell. We left Blandford with the long journey to Plymouth before us, and in arriving there, proceeded to embark on the troop ship HMS Ivernia (sunk by submarine UB 47 Jan 1917~ RJH) which was aside the quay waiting for us. There were several other troopships, so it was a very lively scene, boarding the different boats.

I might mention that our own Company (A Co Benbow Batt) was going on in advance of the other three companies. We got on our allotted boat, and found it was a mixed affair, for there was one company of the Hawke Batt, and the whole of the Collingwood Batt, and a few Engineers.

We stayed at Plymouth for a few days a most miserable time for us on board, as we laid in midstream, and it was horrible hanging about, after we had left dock, but we eventually sailed away about 12-30 at night. Under cover of darkness we got well away to sea before daybreak, escorted by the destroyer, HMS Lucifer, and HMS Loyal. This was a new experience for me, sea all around, and the only thing left to do, was to get used to it. We did not encounter bad weather going through the Bay of Biscay, and that was a good thing too. About here our escorts blew their sirens, as a sign of farewell, and good luck, and then we travelled on our own. It was about this quarter that a sharp lookout had to be kept, on account of submarines. The first four or five days I suffered terribly with a vaccinated arm accompanied by sea sickness, of which the latter is a most awful thing to have, I can assure you.

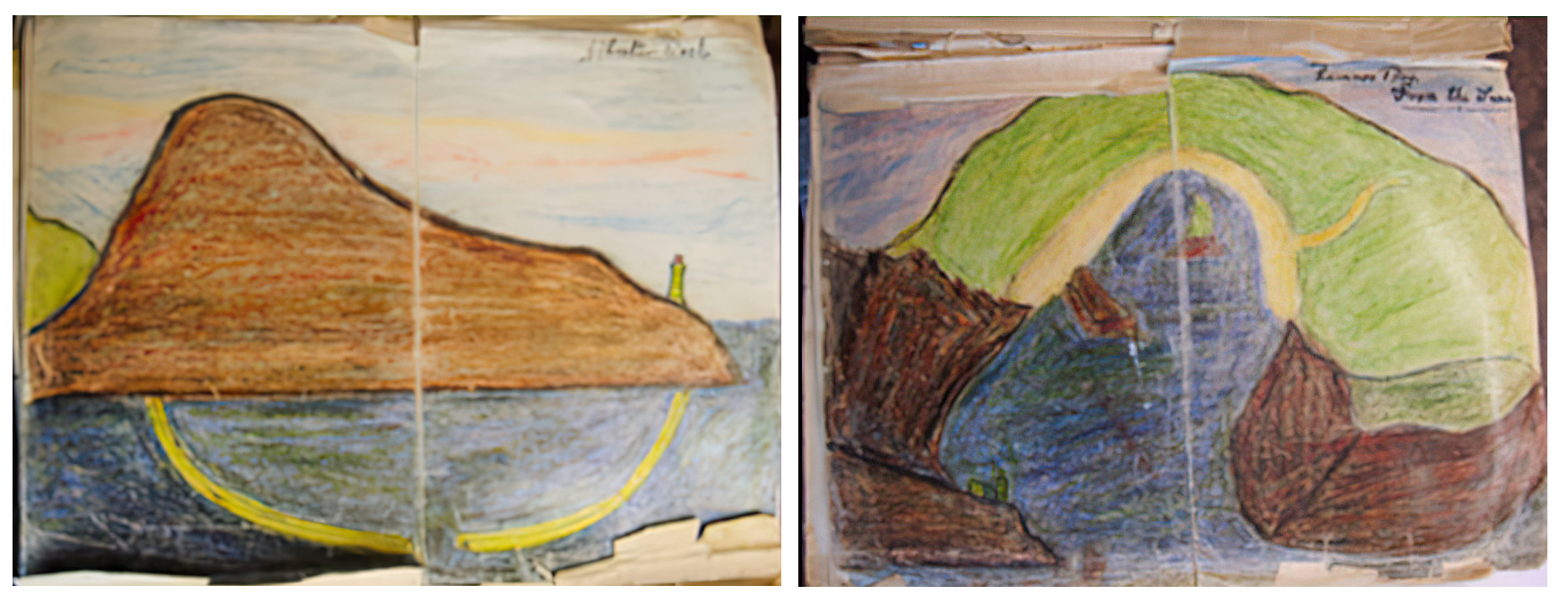

We arrived at the Gibraltar Rock on May 15th safe and sound, after days of dodging submarines. To illustrate this rock, it stands a tremendous height above the sea level, and resembles a huge lion lying down. We stayed there a few hours to get orders where to go next, and then left at 4-30 p.m. the same day. I was getting settled to all the conditions one has to put up with, on a troopship, and the sea was so calm, just like sailing on a sheet of glass.

The sun was getting much hotter, and at first, took some getting accustomed too, for we could hardly find shelter from the heat. After three days on the high sea we sighted land, which was the coast of Sardinia, and here we were forced to get well inland, having been chased by submarines.

On May19th we arrived at Malta, and stayed there until next day. We coaled the ship here, or rather the Natives did, and well we knew it, for although we did not do any, we were as black as Niggers, (common term for black people in 1915 ~ RJH) owing to the dust flying about. At Malta there is a very good harbour for all sorts of shipping, and from the water one has to look high, to see the town on the hillside. We made our departure from here 7-30 p.m. May 20th for our next destiny.

Still going strong we started getting in among the Grecian Archipelago's (some islands) after which, travelling for two days we found our way safely to Lemnos Bay, arriving at 7 p.m. on May 22nd. Lemnos Bay was formerly part of the Turkish Empire, but on the outbreak of the war was claimed by the allies, also Mudros, which was chiefly inhabited by Greeks.

The next day we all went ashore, to get a little exercise, as we felt so stiff lying about on board ship. It was not a nice place to visit as the place was in a horrible state, for all the old refuse was lying about the streets, and it caused such a smell, due no doubt to the heat of the sun. We went for a short route march in the country, and here we saw workmen on the land, using the old time plough, drawn by oxen. It was getting dinner time so our Commander called a halt. We were supplied with bully beef, and hard biscuits, but the former was in a bad state to be given to us, for the heat of the sun had caused the fat to melt, so it ran out like water. After this, we made our way back to the village, where our Commander told us we could have an hours [sic] leave to look over the village.

Mudros was being used for a hospital base for Australian wounded soldiers, also there was an interment camp with hundreds of Turkish prisoners, and this place was surrounded by barbed wire guarded by soldiers. It was a base for the French also. After seeing all the sights we made for the harboured troopship once more, this change had broken the monotony, which was beginning to tell on us. When we got back to the ship we were told that this was as far as we should be going with her. The Collingwood battalion left first, and we followed soon after.

I will try and relate my short but very trying experience in the campaign of Gallipoli Peninsula, which after terrible fierce fighting, our troops were eventually forced to evacuate.

We left the troopship Ivernia at a place called Lemnos Bay and continued our journey, a distance of about sixty or seventy miles, on a smaller ship, (HMS Hythe ~ RJH) as it was too dangerous for the troopship to go near the war zone, owing to enemy submarines, which were very plentiful in those waters. The first thing that so impressed me was one of our warships, which a few days previously had been sunk, and all that could be seen of it was just the keel sticking out of the water. It was a green colour, and at a distance looked like a porpoise just jumping out of the water. The Majestic was torpedoed very mysteriously, and was very near the coast when done. It simply turned completely over, and I should imagine stands upside down on its mast, a very good sight to see.

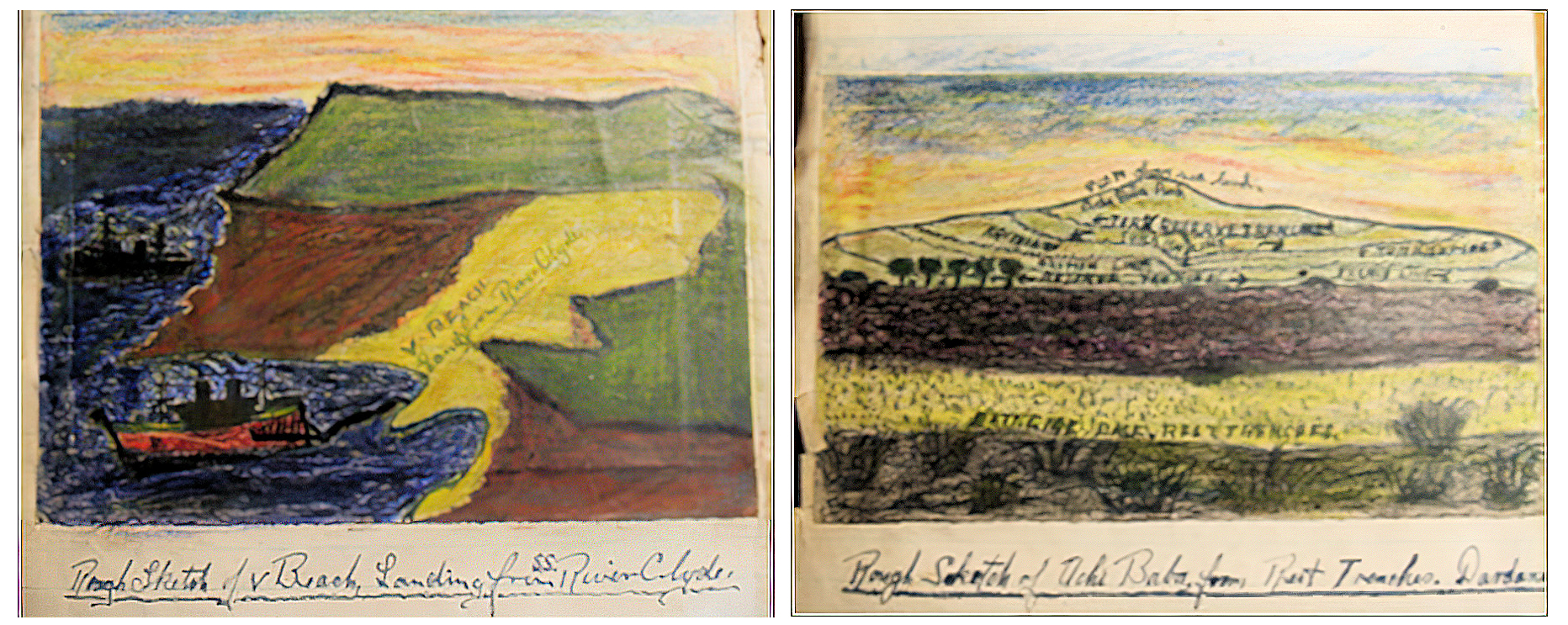

On passing this wreck, we landed on the famous V Beach, by way of the well known ship River Clyde, which was run ashore in the first landing (25th April 1915~ RJH) to help cover the troops while landing. From the string of smaller boats which ran from the Clyde to the shore, forming a kind of bridge we were able to get to the shore without having to wade. The River Clyde has been termed the Ship of Troy on account of the splendid way it was built. After landing from this famous bridge of boats the picture presented to me was very grim, and it seemed to tell me that our business here was going to be somewhat of a serious nature.

It was on Sunday morning May 25th 1915 [sic] (Sunday falls on the 23rd or the 30th ~ RJH) that I made my appearance on this famous peninsula, just as dawn was beginning to break. It was a general thing for the Turks to send over their morning 'Hate' (as we called it) by severely shelling our landing place, but on this particular morning we had rather better treatment.

From the beach we went forward to our position in the Naval Brigade lines, and on our way we saw the splendid work which had been done by the battleship Queen Elizabeth, Turkish forts were smashed (Sedd el Bahr? ~ RJH) to the ground, showing the terrible weapons of war, in the way of guns. We could also see the spot where such a large number of our Gallant Irish, 29th Division, lost their lives. (Dublin Fusiliers? ~ RJH) I was told there were eighty to a hundred all buried in one hole together, and a large cross was erected on this grave to the memory of the brave heroes. There were many other graves with crosses, just to mark the spot, and [sic] name, of others who had fallen. This cemetery was surrounded by barbed wire to keep the horses from straying over it.

We arrived at our allotted position, and orders soon came round to dig in as quickly as possible, up to this time I had not heard the noise of a big gun firing. We were not very long before we were hard at it with pick and shovel, but the ground in places was like a lot of rock, and this made it very hard work for us. We had to dig our dugouts five foot deep, I had got about two feet down with my little hole, when all of a sudden our officer shouted his very loud order to lie down, and to get as much cover, and no sooner had he given this order a large Turkish shell burst into our lines. This was their morning hate to us fresh comers. For about three hours they rained shells on us, and we were working our hardest to get our dugouts done, so that we could get better cover from this rain of iron. At last we managed to get these done, but not without any casualties, as some were killed or wounded. This to me was something new, and I must admit made me feel very shaky for the terrible screaming noise was an awful sensation, as they shot very close to my dugout, sending up huge clouds of smoke and gravel sky high.

After a time I began to wonder where the British, and French were holding there position. Away in the front of me, (see south of the of the Krithia Road trench system? ~ RJH) about six miles was a huge hill running right across the peninsular and appeared to me like another Gibraltar, an impregnable position, held by the enemy. This hill is known as Achi Baba and stands at a height of 860 feet above the sea level, giving the enemy full survey of the land in front. Knowing every inch of the ground we had taken from them, they could drop shells wherever it was their wish. The nature of the country was very rugged, and proved a difficult task for our troops, as the land to them was strange. This was the hill we were trying to wrest from the Turks. On my left I could seethe remains of what was once a Turkish village namely Korithia. [sic] It had been smashed to pieces in the first bombardment of our battleships. All that remains of it are a few ruined walls. Of this village I cannot say much, but one thing is known that our soldiers entered the village but could not stay there, as the stench arising from the dead bodies forced them back to former positions. I might state that the majority of the inhabitants were woman and children, the Turks would not allow them to escape thinking that we British would not shell the town while they were there. Also to my left I found out that the famous 29th Division helped by the Gurkhas, (6th Ghurkhas? ~ RJH) with the Naval Division, holding the centre, comprised the British Lines. The French were holding the position on the extreme right.

This is how I found things, which was none to pleasant I can assure you. The first thing of importance that happened was a Battalion of the RND 'Collingwood' going into action. On the 4th June, there was a general advance towards Achi Baba, and it was in this advance that the 'Collingwood' Battalion was annihilated in a battle for several trenches. It so happened that the French were forced to retire leaving the right flank exposed which the Turks were quick to find out, then they very soon enfiladed (a position in which troops are exposed to gunfire along the length of their formation. ~ RJH) the trenches, the unlucky Battalion had gained. At last they had to fall back, those that were lucky enough to be alive, very few ever returned and were up to the time I came away, still lying in the open, waiting to be buried.

It was an awful day for the division, but credit was all due to those poor gallant fellows. They had only been there just a week, and they were called on to do this job. We had hardly got used to the terrible noises, it was just luck that our Battalion the Benbow's was not called upon, but we should have done our best, as that fated Battalion did.

The next day we had orders that we were to move towards the firing line. We had sand bags issued to us, also ammunition, as much as we could carry. The next [sic] we had was either a pick axe, or shovel. Well at last we made a move towards the trenches, but not without Johnny Turk seeing us. We had about four miles to walk in the open before we reached our destination. The Turks as soon as they saw our movement began to shell us heavily, and it was on this occasion that we lost many men, and officers. I admired our old Colonel, for while under this heavy rain of shells he walked on encouraging us to follow. I was marching in the first four lines of the Battalion and to see this old man still carrying on, one could see he had been under fire, in other earlier campaigns. I did not like the new experience at all, as the shrapnel (metal balls or fragments that are scattered when a shell, bomb, or bullet explodes ~ RJH) was bursting near me. One of our officers was trying to tell us that it was only our own shells, but he never forgot to take cover, and look after his own skin. We were just finding out for ourselves where the shells were coming from so we did not take much notice of what he said, as it was a case of Jack look after your self.

At last we arrived at the gully, which afforded us a shelter from the shells. It was here that we came into the vicinity of bullets, and also where our Colonel (Col Oldfield 5th June ~ RJH) got a bullet through his knee [sic] which caused his retirement from the scene of action, for a good long while. This day seemed to be the finishing up of the Benbow Battalion, although we had not been in any charge the shells bursting among us caused as much damage. The next day we reached the firing line and the sights that I witnessed there, I never want to see again. They were just bringing down the wounded that had fallen in action the previous day, and being fresh to me, I was very much impressed by the sight. I was standing in the trench in the firing line waiting for our next order, when a Turkish shell burst over scattering bullets every where. In this case I was very fortunate as a bullet just grazed my nose, and shot into the earth, doing no damage whatever, but I can assure you I moved away from the spot.

I next found out that we were up there to do fatigue work, if required. It was the officer of one of the Army Regiments who soon gave our officer some thing to do, and the dangers of the work was immense. We were in the trenches that had been taken from the Turks the previous day, and when it got dark it was none to pleasant, as we could still hear the moaning of the wounded who had gone too far, and unable to get back again. To try and help them was too risky, so they had to remain there. At any time the Turk's were expected to make a counter attack, to gain back the trenches they had lost.

Now and again some poor nervy fellow, who had been in action, would call out, and say the Turk's were advancing. The next we heard was that one of the regiments was running short of ammunition, so we were ordered by our officer to pass ours along, shortly after our sandbags as well. We next received, fix bayonets, and told to be prepared, but thank goodness Johnny Turk never came, as I had not got used to things yet.

Our next job was to go out in front of the firing line, and to dig out a communication trench, with orders that as soon as the Turks sent up their starlight's, we were to fall flat to the ground, so that they should not see us, and what we were doing. We were well away with our dangerous task, when all of a sudden up went the lights showing all so clearly about us. We were only twenty five yards from the enemy trenches, so we had to be very quiet, and careful. There were dead lying all around us, and to have to lie down, and find yourself among them was simply ghastly. We had about an hour of this, and we were told to come in. Our officer in charge on hearing where he had been with us said he would not have walked about so easy if he had known. It was a great relief to get back to the firing trenches once again. It was managed very well, and without any loss.

The first young fellow that I personally knew was shot in the head while proceeding along the line, the next day it was my duty to help bury him, as he was one, of our section. We did our best to make a good resting place for the poor unfortunate fellow, who had been such a short time in action. The officer read a portion out of the bible over him, and to see us four standing round his rough grave, would, would bring the hardest man to tears. It brought it home to us, our own personal position, and for myself I felt grieved, and a few tears came to our eyes, as we saw the last of this young fellow, so young, and enjoying good health. It made me think who would be the next to answer the call. After the little ceremony was over we placed a roughly made cross on his grave, bearing his name etc. Shells were falling around us all the time, while giving our last duty to one of our fallen comrades. We then made for our dug outs and remained there for two or three days.

A party was then called out to locate snipers, as several of our lads had been sniped off. I missed that party, but was told off for a night work party, which is far more dangerous, as the Turks are firing all night, and stray bullets come over in galore. My job that night was to help take huge boulders up to the firing line, to make new redoubts. (A redoubt is a shelter with a circular trench round it, where messages are received from general headquarters Redoubts are mostly guarded by about twenty men who are not allowed to let anyone enter the shelter. They are usually just behind the front firing line, and it is the duty of the twenty men to hold that position, even if the troops are forced from the trench in front of it. It is a responsible duty, and if the occasion does arise one has to fight for dear life.) We got about half way with our heavy loads, and the bullets came pouring down about us. This was the first time we had been in this part of the firing line, so our N.C.O. had not the least idea where we were going. Had it not been for one of the 'Old Stagers' coming along, we should have walked right into the hands of the Turks. We were all jolly glad when this job was over, and when we got back to our quarters the N.C.O. in charge, complimented us on our splendid discipline, under such trying circumstances.

We had not been there very long, before we found out that to get a good night sleep, was absolutely impossible. You are told off to go on guard, and as luck would have it, in my case, it was always a watch between 1 o'clock am, until 3am, just the hours when one has to keep a sharp look out for any movement of the enemy. All this time we were between the firing line, and what is called, the rest camp, and the very base. Then came the order that we were to move to this rest camp, and it was received with great joy, as we knew that there, we would be safe from stray bullets. On our way there, it was a very common sight to see mules lying about, that had been killed, by the shrapnel.

We arrived at the rest camp feeling done up, I might mention here that I had been 9 days landed from the ship, and up to this time I had not had a wash, soap and water were both very scarce, but never less I made this my first job, despite the many drawbacks. I might also add that the drinking water was very bad, but owing to the terrific heat of the sun we were forced to drink it. The bully beef, and biscuits were very hard to digest, but we soon got used to all these difficulties. Our breakfast usually consisted of a very salt piece of bacon, and a little tea, and sugar, with a biscuit, and some bully beef for dinner (no desert.)[sic] For supper we had more biscuit, with cheese, if the sun had not melted it during the day, or the flies had not eaten it. Now and again we change our menu, by smashing up some biscuit, mixing it with a little water, boil it for a few minutes, after this, mix with a little of the famous plum and apple jam. All our meals were very salt, which compelled us to drink more water than we should have done. Now and again we had a fly stew, as we called it. We were going along fairly well when one day we noticed a stir in our lines. On enquiring, we learned that owing to our Battalions having such heavy casualties, we were to be put with another Battalion, who also had heavy losses, to make one strong one. This news seemed to upset the old lads, as after being so long together they did not care about being parted. We had got used to all our officers, and anyone can imagine how we felt when we said good bye to our old mates, and officers. I was transferred to the Nelson Batt. And the only thing left to do was to get used to it, but I soon found out that my lot was by no means easy. (? 9th June ~ by RJH)

We were soon shoved off to the trenches digging nearly all day long, doing guard duties at night, and not a bit of peace. It was nothing but hard work, for when we were not digging, we were holding the main firing line, against attack. The first attack that I witnessed was an attack made on a Turkish redoubt, by the Hawke Battalion RND. The position we held at the time was, Nelson Avenue, (19th June see trench map facing page 139 & 140~Royal Naval Division by D Jerrold ~ RJH) and was a very awkward place to deal with an attack, on the Turks. We had orders to fire at a certain spot which all of us thought was a very bad move, but found out that it was a very good one.

The attack was supposed to come of about twelve o'clock. It was pitch black, and I could hardly see my hand in front of me for it was my turn to go on guard from 11pm to 12pm. We had to be very careful, when looking over the trenches because at night we could not use a periscope so one has to pop his head up quickly, look around, and down again, like a jack in a box. I had just done this when it seemed to me that the Turks were getting uneasy, and bullets were coming over faster than before. I went on my guard. All of a sudden a loud cheer rent the air. The Hawke Batt. (Co A ~ RJH) had crawled within 50 yards of the Turks trenches, and then made a final charge. It gave me a fright, as things were so quiet before. Then bullets rained all over the place, the Hawke's got in the redoubt, and we fired where we were told. In the morning we saw a sight we did not bargain for. When the Turks retired from this point, they were forced to go down a gully, then up again to the open, to a communication trench. Johnny Turk did not think we were training our fire on this point, and when he came into it, he never got through. It was nothing, but a mass of dead, and in the open on a slight slope, and could be seen for miles, quite plainly. There were a lot still in the deep gulley (which is more like a deep pit, caused by the rushing of water, when the monsoons come on) waiting to try, and escape, but it was now daylight, and they were all finished off, as the day went on.

The next few days the Turks gave me a little idea of his fighting qualities. A big strong Turk came out with his coat off, and his sleeves turned up. He was a bomb thrower, (Grenade thrower. My other Grandfather, was also a bomb thrower in the Royal Sussex Regiment 13th Battalion ~ SD 3724 Charles Woolford. He was honourably discharged on the 14th Jan 1918, after being wounded ~ RJH) and seeing this we allowed him to get near the redoubt, and then the whole Nelson line opened fire on him. He dropped like a log, never to rise again, such pluck, and daring is just as frequent with the Turk, as in our own army. They attacked this position they had lost several times, which eventually, we were, forced to retire from, after holding it about four days. It was hard to have to give way, but during their attacks, we had suffered heavy losses, and we gradually got too weak to hold on. It was the Turks [sic] redoubt again, after heavy losses on both sides. I might mention here that the time spent in the firing line is eight days, then a supposed rest at the base, and up at the firing line again. When we went from the firing line there was nothing else to look forward to, but a week of hard work, either digging, or blowing up large lumps of rock to make trenches. If we did get any time to spare we would be seen killing flies, and fleas, which annoyed us very much. The same routine was carried out at the base, as regarding doing night, and even day duty. Some nights I was on guard, and it was a strange feeling in the dead of night to hear the pitiful braying of the horses even they, seem to understand the danger they are in. The food was getting horrible; the weather was so hot that the bully beef ran out of the tins like water, giving one very small appetite to eat such stuff, but we had to put up with it best we could.

The sleeping accommodation here was a kind of open air treatment as the only cover we had was the sky over us, and well we knew it when the rain came down. When a cloud bursts in an Eastern country it seems to fall in buckets full at a time. These storms generally come at night, and if asleep, you wake up and find yourself wet to the skin, a very uncomfortable feeling I can assure you, but one advantage is that it is soon dried by the heat of the sun. It is a beautiful sight to see the sunset, and many a time, when at liberty I have watched it, this grand scene of the sun sinking in the west. I had not got a watch to tell me the time, so I used to get my time, as near as possible, by the sun. At night I used to get my bearings by the Great North Star then I knew what part of the globe I was on, and where the old country was situated also.

Having gone rather a long time without a wash, we thought one day that a bathe on the shores of the peninsula, would not do us any harm. The Turks however managed to see us, and gave us a few shells to get on with, but we managed to get across the plain to the water quite safely. The scene here was not very inviting however, for dead horses were floating about in the water, but these things did not trouble us long, so in I went with a crowd of the boys. The Turks were soon quick to notice us in the water, and were perhaps a little jealous of our weekly wash. They killed two of our lads in the water, and I was not long before I was missing from it, never to go there again for a wash.

Our week of rest was over, and back again to the trenches we went. Every week there was some big engagement, so we always had the idea that we were going to see something. There was a general feeling that it was much safer in the firing line, than it was at the rest camp, for the Turkish guns could not manage to locate the trenches, but they knew every inch of the base camp.

All went well the first few days, but early one morning it would be getting about daybreak our artillery, and the French 75mm guns, also our battleship, opened fire on the Turks [sic] front line position. It was nothing but a rain of shell into their trenches for about four hours. It was a terrible cannonade, and then just as the sun rose over the hills the order came along the line to fix bayonets. This was done and made a beautiful, but gruesome spectacle. The bayonets glittered in the sun, and were showing over the top of our parapets, right from one end of the firing line to the other .This ruse was done to frighten Johnny Turk, also so that he would not know from where the advance was to be made. It proved to be rather a good one, for the Turks had to man the whole of their front line trench. It so happened to be the French, who had to make the advance and so they did and Johnny was caught napping this time. I was in a very good place to see the Turks make a counter attack on the French, and drive them back a trench. It was from here that I saw the splendid powers of the French gunners with their famous 75mm. The Turks again attacked, and were coming forward in a mass; all huddled up together like a lot of sheep. One could see that they were being driven out to make an attack. They were allowed to get half way across right out in the open, then the guns played havoc, and the whole line seemed to stop dead, not knowing where to go, or what to do, for shelter. It seemed as though hundreds were being blown sky high, and very few ever got back to their trenches again. A few did get across, but they were forced down the R.N.D. lines.

This is where a terrible thing happened, for the Turks jumped into a trench held by the Anson Battalion, and in the surprise several were killed, and badly wounded. This Batt, earned a very good name in the first landing, but was very much disgraced for not keeping a sharper look out, on this occasion. The Turks that paid this surprise visit were soon finished off in their hasty retreat, as we had a very good view of all that happened where our Batt was engaged. For hours, after this engagement the Turks were seen to be running all over the place, they simply lost their heads it was a rough time for them. I know after that, I thought I would have something to eat, but when I had got it ready I seemed to have sickened against it, after what I had seen. I also had a very heavy mail come to me at the time, and my thoughts were if they were to see such goings on. I know it was the picture of the flags of the Allies, and the British bulldog, that impressed me a good deal, and so those exciting moments soon past from my mind.

So our time passed on and then away back, to the old rest camp again, to be in fear of the shells finding you out. As I have mentioned before rest for the troops on the Peninsula was very scarce, one could not sleep in the daytime on account of the worrying flies, and more so the terrific heat of the sun. About this time I had a very narrow escape, while sitting in a crevice in my dugout. A shell from the Asiatic Coast, which we called 'Asiatic Annie', burst right over our camp, and a large piece came down and tore the sleeve of my jacket, then, buried itself about a foot deep in the ground. My chums rushed up to me, to see if I was hurt, but happily I was still smiling although somewhat shaken up. Some of our lads went under with the same shell, it was the nearest I think I had, but good fortune still favoured me.

It was about this time when I was very much annoyed with the Turks, for as I have mentioned before, they gave us every morning a good shelling, by way of saying good morning, which was as good as an alarm clock, and we did not need a second calling. Their morning hate on this occasion was worse than ever before. Breakfast time came round, and we began to get hungry, but still they were at it, so we got our little fires going, by means of just crawling out of our dug outs. I had got my little canteen of water on the boil, for a cup of tea, also a piece of salt bacon, with a biscuit soaking in the fat, when all of a sudden we heard the scream of a shell. We all made one rush for our little holes, and in the melee my breakfast went flying in the sand. I was not the only one who had this misfortune, and of course we all had a general laugh over the scuffle. Having no more wood, (which was very scarce) I could not get any more breakfast, so my chum who had had better luck than myself, invited me to share his meal.

The days at the rest camp passed on, and we seemed to lose count of the days, but we could always tell Sunday, as more often big attacks, and artillery duals, took place. Sunday arrived at this particular time, and I was told by a young fellow that a Wesleyan chaplain was holding a short service at six o'clock in the evening. It was a long time since I had been in touch with this gentleman, so I thought I would go and hear him speak a few words of comfort. I managed to get to his little place, and found it was right in the open, in full view of Achi Baba, but we found a better shelter in a dug-out. He told us that he took a great responsibility holding this short service, and if we heard any shells come screaming over, to make for the cover, we found best, We had our own little books with us, so we could choose any one we liked. Of course we chose all the good old hymns and started of with Nearer my God to Thee, then O God our help in ages past, and when it came to, Time like an ever rolling stream, bears all its Sons away, we all seemed choked, for it brought back old times and memories of the dear ones left behind, and we knew that at any time the call might come to anyone of us in that isolated place. We got through the singing alright, and then the chaplain spoke to us for about five minutes, not a sermon, but good sound advice, which we all enjoyed very much. The little meeting we ended up, by singing a good rousing tune. When the roll is called up yonder, this cheered us up for the next day, we were to carry on to the firing line again, and it gave us courage, so I left the meeting very much better for having attended. The Turks never bothered us much, for which we were glad.

When I got back to my little dug-out, my chum told me, he had heard us singing and wished that he had been there also, I knew just how he felt for I had had the same experience. I had heard singing, but it was too far away to be able to get at. It is very strange to hear the singing of hymns on the battlefield, for the music seems to resound everywhere for miles around. That was the best Sunday I had enjoyed, for months past. When we got back to the trenches there was a rumour that the R.N.D. were going to be withdrawn from the trenches altogether, which of course cheered us all considerably as many of our Batt were old sailors, and they wanted to get back on board again. Weeks passed, and we were still taking our turn in the trenches, until at last we gave up hope, and although we heard the same rumour again, it went to the wind.

The strain was very severe, being all work and no play. When at the rest camp it was a case of watching the sky, as now and again, there might be a little excitement, caused by a duel in the air. The Turks liked potting at aeroplanes, but in the meantime they did not forget to send [sic] over to us, as well, quickly ending our excitement as we made a move, for it is a case of bob down your [sic] spotted. Occasionally German Taubes (German reconnaissance aircraft ~some troops used it to describe any German aircraft ~ RJH) would fly over us, and drop bombs and scraps of paper, with advice, telling us to either get off the peninsula, or be driven into the sea. It also stated that we were losing terribly on all fronts, but this German bluff never served, to put the damper on our feelings.

We were not allowed to leave our dug-outs, and as there were not any shops out there, we could not get anything to make a change in our diet. So that is how we used to live, more like rabbits, for if we heard any shells coming, down our holes we would go. It was really laughable to see us sometimes, but very serious, if any of the shells found one of us. When we wanted to get a supply of water, when in the firing line, we would have a dig about nine inches square and three feet deep. Then leave it for a while, but occasionally our labours were in vain. Some of the water was quite clean, and some was a milky colour, and also dirty, but this did not worry us long, if we were in a hurry for a drink. It was very often the case that we ran short of water, and then parties were told off to walk about two miles, and get some, where there was a fairly good supply of it, pumped from a well. The water was brought up in large skins, which are used by all the people in Eastern countries, for carrying water. I can well remember being told off with a party to get some water, but instead of using the skins we brought it in biscuit tins. The supply was in the open just near a shrapnel gully, so all the proceeding party had to keep well out of sight as well as possible, for the Turks has a very quick eye for any movement. We got along to this gully, and while waiting for fresh orders, put down our tins, very much in the open, not one of us had had a wash for several days, and as there were a little stream running by, we took advantage of this few minutes rest, We did not have any soap, or towels with us, but the water was very refreshing on such a hot day, and we made use of our handkerchiefs for wiping purposes.

This done we thought we would have a lay down, and some of the lads had got nicely settled, but not for long, as our biscuit tins had given us away. The sun, by shining on the tins, had attracted the attention of the Turks at once telling them that we were going for water. They made it their business to stop us, and the next minute were sending over shells in galore. The first one that came over to us told us we were spotted, and the scene was soon changed, from one of peace, to confusion. Some of our party lay flat on the ground, while I with a few others found ourselves up to our knees in the stream, taking cover under a piece of rock that jutted out over the water. Shrapnel bullets were spitting about all over the place and in the water as well. In the interval of the shells coming over, all my mates had disappeared, and I found myself in the water alone. I soon paddled after them, as fast as my legs would carry me, in the hope of finding them. When I did find them, they were all protesting about going to get the much needed water, and as we had lost our N.C.O. in the melee we decided that the water would have to be got on some other occasion. Johnny Turk had scored a point with us that day, and also spoilt the chance of a much needed rest.

We had just finished another week in the firing line, when our officer ordered us out to the different trenches in the firing line, to give them a good clean up. The Navy has always been known for its cleanliness etc. and so were we, when ever we occupied any part of the firing line, for we still kept up our good points while on land. This job done, we were told that our trenches were being handed over to the army. So we left the lines spick [sic] and span. We learned after that a Scottish Regiment were to take them over, which rather pleased us, for they were a fine big lot of fellows just fresh out, and new to the life. One Scot said to me Jack, where is that hill they want taken, and of course I looked at him thinking he was trying to pull my leg. True I well knew what he meant, and pointed to Achi Baba. I knew, but he didn't, how we had tried for that position, and how in vain it seemed. Well he said to me, "that wee hill yonder" and I nodded my head, so he said, "The Scots will take that for you". So could we have done, if there had, been a camera handy, and we left the Scotchmen to do their best. How we thought we were in for brighter times, but things were getting very serious in the fighting line, and we were done again.

On the fifth night that we had been out in the trenches, orders came, that each man was to have as much ammunition as he could carry, two small sandbags, and a pickaxe, and to be ready to move off at 2am. We all looked at one another in surprise, and began to enquire what was doing. When the time came for us to be on the move we found out that we were required in the firing line. This news did not cheer us much for what with being very tired, and having heavy loads to carry, we looked more like beasts of burden, and felt more dead, than alive.

While on our way up to the firing line we came across a few hundred Turkish prisoners being escorted to the base, and we learned that the Scots had been in a smash up with them. I looked for the Scots on Achi Baba, but they had done their best, poor fellows, and had also, no doubt, found out their mistake. On going up to their position we saw sights enough to turn a man out of his mind. We saw where the poor fellows had crawled away to die, and we our beautiful clean trenches like a pigsty. The Scots had done very well in a charge on a position, we had tried for months to get, but they had suffered terrible losses.

At last we got to our well known places and were told the places our army had captured, and to keep a sharp look out. We had been in the line about half an hour, (12th July? ~ RJH) when I saw the Scotchmen returning from their position for all they were worth. They had been holding a Turkish trench, and got panicky, and turned, and ran and we thought, they were going right down to the beach. One of our officer's [sic] seeing this dangerous move, leapt over the parapet, and went over to these poor fellows, and rallied them, amidst loud cheers all along the line. He gained the highest award for this brave action, but was afterwards found out, to have received fatal wounds. For nine hours he suffered acute pains, and then died. This happened early in the morning, and little did we think we should be travelling over the same ground in the afternoon, but it was as well that we never knew. As the morning went on we gradually moved away from our old lines, and went away as if we were going back to the base again, but we soon found out our mistake.

All this time we had been on the move, without the least chance of getting a snack of food, and the last we had was the day previous. We had got one bottle of water each and we had to go sparing with it. We arrived at Shrapnel Gully (so named on account of so many getting knocked out there by shrapnel) and passed it safely, to find our selves proceeding to the lines that the other Batts of the R.N.D., had held next to the French. These trenches and the ground in front of them were all unknown to us. Well, we managed to get along to the front with a lot of trouble and on our way passed several Turkish prisoners, being escorted down to the back of the lines. We stayed there for about four hours and we were not allowed to start to get any food for ourselves, neither did we know what was going to take place. (Nelson Batt moved to Backhouse Post during the night 12th/13th July by ~ RJH)

The French and the British artillery began to get stronger and stronger in sending out their shells of death, until the noise was so deafening, you could not hear what the next man was saying to you. The poor old Scots, (Highland Light Infantry? by RJH) had been forced to retire from the trenches, they had gained, that was why such a cannonading was going on. But we did not know anything of this; all we did was to lay [sic] down at the bottom of our trenches, for cover from our own guns, which were bursting near us. Since then we have learned that our own Colonel had offered to make a charge with his Battalion to regain the trenches the Scots had lost.

About 4-30 pm an order came along the line to be prepared at any time, to move off, and we thought that we were done for the day, and going back to our resting base. But no, we were going back to the front firing line, and when we got there the shells were bursting in the trenches, and upset us a bit. (Attack carried out by Nelson and Portsmouth Battalion? ~ RJH) Then an order came down, to fix bayonets, and over the parapet, when the whistle blew, followed by another order, to go over two trenches, and hold on to the third at any cost. (Tuesday 13thJuly ~ see page 143 Royal Naval Divisions ~ RJH)

I turned to an old chum of mine, and said "Its come at last", and shaking hands, and wishing each other the best of good luck, over into the open we went, many of the poor fellows only just got out the trench, and before they had a chance to run were, either killed or badly wounded. I cannot say how it was I missed such a fate, but I simply kept running, and I certainly was not in my right senses. I came to the first trench without getting hit, and beheld a terrible sight. All I could see was dead bodies, and I could hear the dying calling for water, but all I had in my head was to get over two trenches, and hold the third at any cost. (See p145 ~ the battles of June & July ~ Royal Naval Divisions ~ RJH)

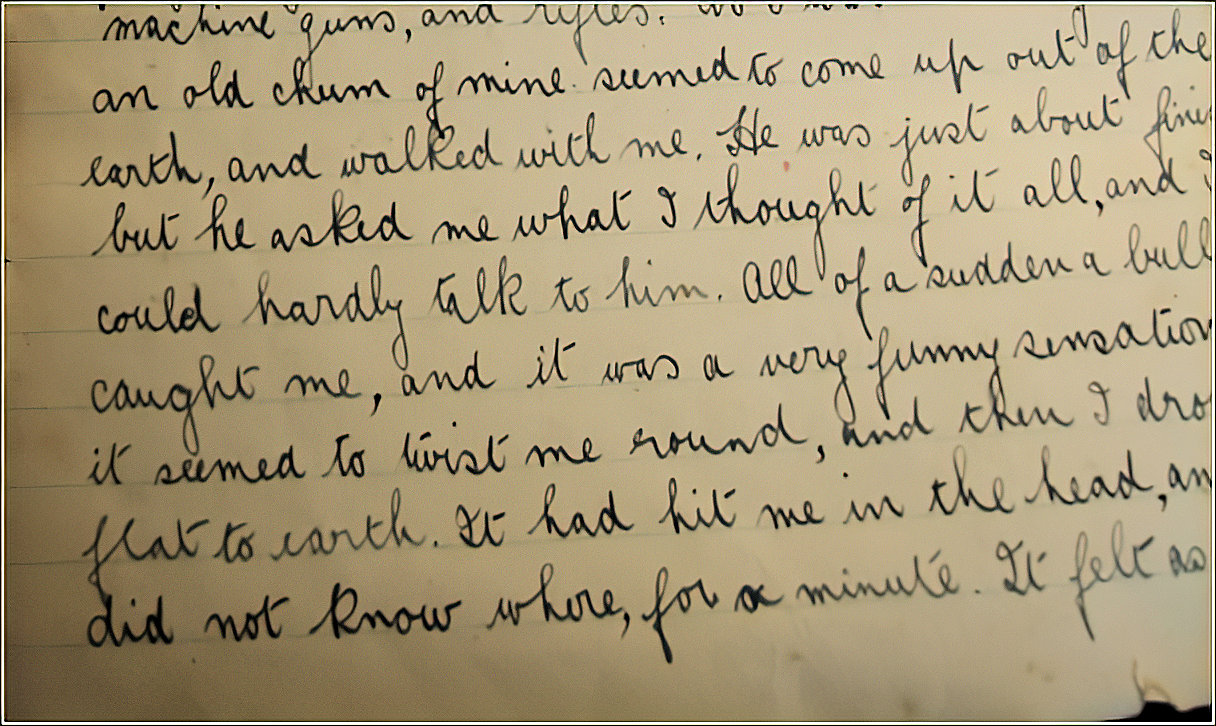

Still running, I came to the second trench, which I believe was a dummy trench, set with mines, so I jumped quite clear of that, and proceeded to the hoped for position. The time I had been running made me begin to feel puffed out, and I began to think that if I went on much longer, at this rate I should soon be on Achi Baba, when all of a sudden I came to a very deep slope in the ground, over which I had to jump. While jumping this little gulf I badly sprained my ankle, and when I got up to make another run for the desired trench I found I could only walk, running was quite out of the question. So I started to walk on again, forgetting the dangers, from the Turkish artillery, machine guns, and rifles. As I walking along an old chum of mine seemed to come out of the earth, and walked with me. He was just about finished, but he asked me what I thought of it all, and I could hardly talk to him.

All of a sudden a bullet caught me, and it was a very funny sensation for it seemed to twist me round, and then I dropped flat to earth. It had hit me in the head, and I did not know where, for a minute. It felt as if it had hit me in the neck, but I found it had gone through my upper lip then into my tunic, at the top of my arm, just missing my arm. I was lying there in the open, feeling somewhat dazed wondering what to do next, so I raised myself just a little, and I saw that the advance trench was about 30 to 40 yards in front, and also a few of my poor comrades lying dead near me. Then I thought that I would make a move towards the trench, but just as I was about to go I heard a rattle of bullets just over my head. I stopped, and to my horror found they were trying to finish me of [sic] with a machine gun. I began to give myself up as finished, when I saw a large hole just beside me, ( made by one of the Turkish shells) which I thought would make good cover for me, but my second thoughts proved to save my life. I had made up my mind to crawl forward and just as I did so another shell burst into the hole. This gave me a good shaking up, but at last I gained my desires, yet still they could not let me alone, for the snipers were still trying hard for me.

When I crawled over the parapet to my horror I saw lying dead at the bottom, the fellow who only a few minutes before, had asked me what I thought of it all. His eyes just rolled over, and closed, so I thought it was of no use to try, and help him. He had been shot through the stomach by an explosive bullet, and it made me think then that if I had not been shot previously, it might have been my fate. There were just a few running about in this trench, that had got across quite safely, and they seemed quite off their heads in excitement, but there was just one officer there to take charge of affairs. I managed to get a rough bandage round my face by a man who passed me, thinking I had been finished; by the way I had fallen to the ground. The first thing the fellows did was to make a parapet, of whatever they could get, and not being able to get enough sandbags, they had to pile up the dead, in front of them for protection. I with a good many others were useless, so we had to lay in the bottom of the trench, until night came. It was an awful time to wait, and we were a good way up in the Turkish lines, right away from our own. The Engineers were sapping away for all they were worth, so as they could join the captured trenches, to our own, and as we had charged at least 800 yards, it was some time before they could reach us.

We were expecting all the time, that the Turks would make a charge, to regain their trenches, but thank goodness they had had enough of it, for one day, and so had we. Being very weak, in the advanced line, we called for help from one of the other Battalions, who soon came to our aid. At last night fell, and all wounded had to get away, as quickly as possible. We had to go a little way in the open, (at least those that could manage to) and then into a trench that had been occupied by the Turks in the morning. Not knowing the ground we were going over, we had to be very careful, for snipers were always lurking about, and none of us carried any rifles. Then we managed after a while to get someone to lead us the right way, and saw a sight that will always be in my mind.

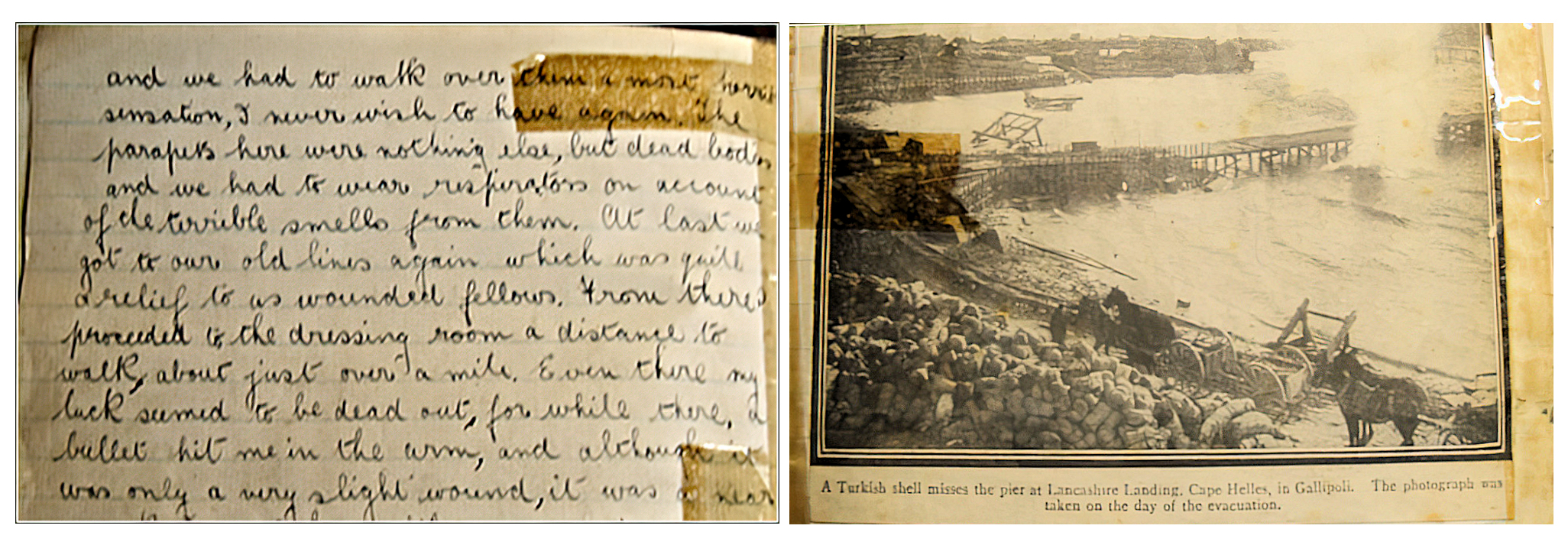

A good hundred yards of this trench was filled with dead Turks, lying on top of one another, and some of our men too, and we had to walk over them a most horrible sensation, I never wish to have again. The parapets here were nothing else, but dead bodies and we had to wear respirators on account of the terrible smells from them. At last we got to our old lines again which was quite a relief to us wounded fellows. From there I proceeded to the dressing room a distance to walk, about just over a mile. Even there my luck seemed to be dead out, for while there, a bullet hit me in the arm, and although it was only a slight wound, it was a near squeak. I went there with one wound, and came away with two, then I was put on an ambulance wagon, and taken to the extreme Base Hospital. We arrived at this place about 1-30 a.m. after a journey of six miles, which had taken us between six, and seven hours, from the gained trenches, to the extreme point of the peninsular. I felt done to the world, and we layed [sic] there till daybreak, feeling very hungry, and thirsty, for we had not had any food for a long time.

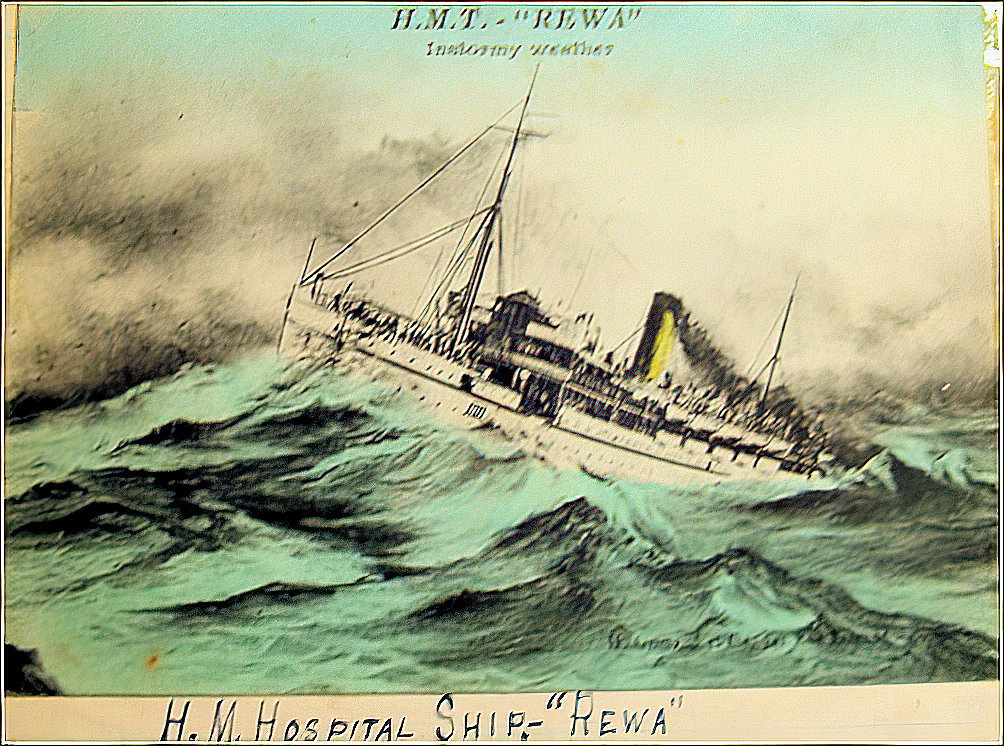

Then we were taken down to the famous Lancashire Landing, and embarked on a barque which towed us, from two hundred to three hundred yards, to the Hospital ship 'Rewa[. While on the way to the ship we had the shells coming at us, splashing the water all over the place, but eventually we got to the ship in safety.

The previous days work had been a glorious one for the Nelson Batt, for we had made a good name, but had suffered terribly. (Approx. 280 casualties in the Nelson Battalion attack on the 13th July ~ RJH) Our Colonel acted very bravely, cheering, and rallying his men in the long advance, for it needed tact to keep us men going under such a heavy rain of lead, but he must have gone too far, also some of our men, and they were either killed, or badly wounded. The condition of things was so bad that they could not be brought in by our men. I was told that the Colonel had gained the D.S.M. [SIC] (? D.S.O.~ the Distinguished Service Order was awarded to Lt Commanders and above ~ RJH) for his bravery, also that he had been terribly wounded, and soon died after he was found, so he never lived to receive the reward, for his noble conduct. (Colonel Evelegh? ~ RJH) One of our Petty Officers was also seen, to carry in several wounded men from the dangerous parts, in the front of our new firing line, under heavy shell fire from the Turks, and he also won the D.S.M., which I had the pleasure of seeing him receive, some six months later at the Naval Hospital, Plymouth. (Distinguished Service Medal awarded to Non Commissioned Officers & men. ~ RJH)

We stayed just off the peninsula for about two days, and then started with about 1,500 aboard. It was good to have a decent meal, and was no doubt enjoyed by all after the living we had been having on land. We were pleased to be away from the shells and stray bullets, also it was a great relief to know we were in a safer place. This puts the finishing touch to my career on the peninsula, where with my other comrades we had spent such a time of terrible hardships.

Our first stopping place was Lemnos Bay, and then we proceeded to Alexandria (Egypt). On the way several of the fellows succumbed to their wounds, and these were buried at sea. After a few days run we arrived at Alexandria, and at the docks were met by a Red Cross train, which was waiting to take us to different hospitals. All the Nelson Battalion that had been wounded, managed to get together, and so we all proceeded to Cairo by train, a distance of some seventy to eighty miles inland. After a few hours ride through very flat country, we arrived at our destination, where we were sent to different hospitals. I was sent to Kas EL Ainy Hospital, close to the well known River Nile. Here we had Egyptian students to attend to us, and they were more bother than they were really worth, but having nobody else, it was a case of having to put up with them. From there I was sent to Narith [SIC] (? ~ RJH) Convalescent Home. My wounds were healing fairly well, but things were not going so well with me, as I should have liked them to.

Weaknesses seemed to arise for which I feared, and I could not rid my mind of the terrible scenes I had witnessed, the last few days on the peninsula, but all the time I went on trying to pull myself together, and not give in. I was next sent from this Home to another, which was called Albassia Rest Camp, (Albassia Hospital Cairo ~ RJH) and was advised to have rest, which I had for the following two months. The Sphinx, Pyramids, and the Dead City, were all the places that I visited, and even those did not interest me very much as they would have done under ordinary circumstances, for nothing appealed to my mind. The last place I stayed had its drawbacks, but on the whole it was fairly good, all were allowed to walk when they wanted, so there was plenty of freedom, for any who wanted it.Then I was told that I was being invalided home to England, as they had not got any treatment, I required. After a terrible voyage, during which, I had a bad time, of sea sickness, that did not improve my state of condition, we arrived safely at Plymouth. I with several other Naval Ratings were taken from the hospital ship, 'Andania' (Torpedoed and sunk by U46 in 1918 ~ RJH) on to a smaller pinnacle, which took us up the river. We arrived at the Royal Naval Hospital in the evening on October 14th 1915, and were then sent to allotted wards for treatment required. I was a patient there for just on four months, and derived great benefit from the electrical treatment that I received. Time seemed to hang very long here, but with perseverance, I began to slowly make towards recovery.

I was then sent to a private convalescent home in Essex, and when I arrived there I meet one of the old Nelson fellows. The strange coincidence was that both of us thought each other killed in the charge, so it cleared our minds on that score, but we had both had a long time of it in hospital. He had got a bullet through the muscle of his arm, and had lost the use of it, but for all that we were glad to meet again. My stay there was a great help to me, getting fresh air and a change of scene, and then the time came for me to go back to Plymouth. The change had done me good, and I had also made more good friends, whose kindness I shall always remember.

On my slow improvement, I was invalided from the service, as unfit to carry on, that sort of business again. I left the Naval Hospital, Plymouth, on February 2nd 1916 for home, but not feeling the man I had been, fifteen months previously, when I joined the Royal Naval Division.

So ends my experience as a fighting man, and one that I never hope to pass through again. Yet I am contented to know that with my other comrades, had tried our very hardest to do our very best, for King and Country, also for the grand cause of Right against Might.

James R J Hart. R.N.V.R.

Late of Benbow, and Nelson Batt.

Royal Naval Division

© 1999-2025 The Royal Navy Research Archive All Rights Reserved Terms of use Powered byW3.CSS

At the end of June 1945, the Admiralty implemented a new system of classification for carrier air wings, adopting the American practice one carrier would embark a single Carrier Air Group (CAG) which would encompass all the ships squadrons.

Sturtivant, R & Balance, T. (1994) 'Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm’ list 899 squadron as conducting DLT on the Escort Carrier ARBITER on August 15th. It is possible that the usual three-day evolution was cancelled due to the announcement of the Japanese surrender on this date and was postponed for a month.

Gordon served with the radio section of Mobile Repair UNit No.1 (MR 1) at Nowra, he was a member of the local RN dance band, and possibly the last member of MONAB I to leave Nowra after it paid off. .

In March 1946 I joined 812 squadron, aboard HMS Vengeance, spending some time ditching American aircraft north of Australia. Eventually we sailed for Ceylon ( Sri Lanka ) landing at Trincomalee and setting up a radio section at Katakarunda. In the belief that we were exhausted we were sent to a rest camp at Kandy for a few weeks. We moved down to Colombo to pick up Vengeance and returned to Portsmouth via the Suez Canal . I was discharged in November 1946.

Comments (0)