Robin Knight describes the life and death of an unsung British hero.

It all started with a brief announcement in an old school magazine published in 1944 that I stumbled across while researching a book. C.M.B. Cumberlege, it stated, had been posted as missing. A month or two later on holiday in Italy I read Artemis Cooper's biography of Patrick Leigh Fermor and came across another reference. On my return I wrote to Ms. Cooper seeking more information. She emailed me to say that she had none but that her husband, the well known military historian Anthony Beevor, mentioned Cumberlege in his 1991 book about Crete during the Second World War.

He had, indeed, not entirely correctly as it turned out. But some good new leads emerged from the book and before long I was delving into a treasure trove of ever-widening sources - archival references, specialist websites, footnotes in reference books and much more besides. The official New Zealand history of the war contained two short citations. The Royal Navy Research Archive supplied Cumberlege's service record. Someone called PhiloNauticus on an RN research site dug up details of awards won by Cumberlege. A search of the London Gazette gave corroborating evidence. Then a message I placed with the SOE (Special Operations Executive) Yahoo group garnered new information from the Special Forces Roll of Honour. In turn this led me one sunny Sunday morning to the Chatham Naval Memorial website. Here I found detail of Cumberlege's death and also, mirabile dictu, two photos of the man himself.

By now I was fully committed to the search. Numerous visits followed to the bountiful National Archives at Kew as I trawled through more than 80 files. I made contact with Cumberlege's son Marcus, a poet living in Bruges. A rummage through back issues of The Log, the school magazine of the Nautical College Pangbourne which had started me on this trail, turned up a moving tribute written by a wartime colleague in 1946 when Cumberlege's death had been confirmed by the Admiralty. And then someone belonging to the SOE Yahoo group told me about Platon Alexiades in far-away Montreal.

Platon, it turned out had long been investigating submarine warfare in the eastern Mediterranean. He, too, had become fascinated with the Cumberlege saga. Even better, he had written an unpublished book. We got in touch, he generously shared his manuscript with me - a quite phenomenal piece of research - and eventually we met in Kew. Meantime through Amazon and Abe Books I unearthed several long forgotten biographies that shed more light on Mike Cumberlege. His story is one of extraordinary daring and bravery in the face of huge odds and unimaginable brutality. It deserves to be widely known.

Claude Michael Bulstrode Cumberlege was born in 1905 into a seafaring family. Both his father and grandfather were Admirals, his philandering, handsome father lived on a yacht in the south of France and early on Mike, as he was known, expressed a desire to go to sea himself. A family anecdote recalls how as a boy he swam across the French port of Bayonne at night and hoisted a chamber pot to the topmast of a passing American ship which had failed to dip its flag in salute to the Admiral's schooner. At prep school in Somerset two doting 'stone-age' ladies called Aunt Gladys and Aunt Gwen stimulated his patriotism with rousing sea songs like "Heart of oak are our ships, heart of oak are our men." Another family story has him singing aloud "Land of hope and glory" in the streets of German-occupied Athens during the Second World War.

At the age of 14 he entered the Nautical College, Pangbourne, to prepare for a naval career. Then just two years old, the College was nowhere near the sea and situated on a hill high above the Thames valley in rural Berkshire. Staffed by a motley crew of rapidly changing teachers and retired upper and lower deck Royal and Merchant Navy personnel, and overseen by its redoubtable shipowner founder Sir Thomas Devitt, the education it offered was basic. But it did its job.

At Pangbourne Cumberlege boxed, played rugby ("he is full of vigour, is not afraid of hard knocks and is a really fine tackler"), won a prize for Geography, showed leadership potential and became a Cadet Captain (prefect) in the Summer Term of 1921 - all clear pointers for what lay ahead. After Pangbourne he did three years with the Aberdeen Line, serving as a cadet on ss Euripides, a 15,000 ton converted troop carrier with 1,100 passengers. This regimented experience seems to have paled fairly quickly. After putting in time on a Belgian fishing trawler in 1925-26, he took his Second Mate's certificate in 1926 and decided to branch out on his own while retaining a foot in the conventional world by becoming an officer in the Royal Naval Reserve.

For the next 14 years Mike lived on his wits. An old Pangbourne chum met him around this time and reported that Cumberlege was "looking forward to a year or more of adventure, going round the world in a sailing yacht, accompanied by a cinema camera." The sea, yachts, poetry and music were his life. He loved operatic arias, music by Beethoven and Brahms and verse by Byron and Gerald Manly Hopkins. His sense of humour was notorious and often expressed in verse such as his Ode to My Best Friend's Nose. Another poem he wrote in the 1930s, Windy Day, gives a flavour of his robust style: "Rude Boreas, old father wind,/Shatters the shutters;/Crash, smash,/Then tears to tatters/Curtain and sash,/All that the old fellow can find..."

Unable to afford the sort of yachts he wanted to own, Mike took to skippering, mostly in the Mediterranean and chiefly for wealthy Americans. "As such, he was one of the fore-runners of the gentleman skippers of today," wrote Robin Bryer in a book published in 1982 about Jolie Brise, one of the boats Cumberlege helmed. "An attractive Englishman, with a good background... mixing aristocratic self-assurance with the professionalism of the servants which his family once employed."

Jolie Brise was to provide the French and Spanish-speaking Cumberlege with memorable experiences from 1934-38. Built in Le Havre in 1913, she was originally a pilot cutter delivering mail before being refitted and winning the Fastnet race three times. In 1934 she was sold to a rich American friend of Cumberlege's father, Stanley Mortimer of New York. He appointed Mike skipper and told him to oversee a total refit that winter in order to make the yacht suitable for cruising. The following summer this unlikely duo and a three-man crew, including a Czech steward by the name of Jan Kotrba, completed voyages around the Mediterranean totalling 7,000 miles. Each winter the boat returned to Southampton.

In 1936 Mike married a "charming, very beautiful Canadian" called Nancy Wooler and the couple settled in a rented cottage in Cap d'Antibes in southern France. Soon after he resigned from the RNR. Nancy, recounted Bryer, sometimes accompanied Mike, who was not one to suffer fools gladly, on his voyages. 'She must have had a moderating effect on the two extremes of Michael's character. On the one hand, he was a poet; on the other a good man with his fists... a cheerful young adventurer." Tough enough, in fact, on one occasion to knock out two crew members of Jolie Brise who went ashore contrary to the owner's instructions.

A sample of Mike's writing exists in a 1935 issue of The Log. There is an almost lyrical tone, if no full stops, in his account of "A Sail That Made A Summer" ... a description of his voyages in the summer of 1935. "I can think of nothing more perfect than the day we sailed out of the Adriatic, the sea breeze blowing into Italy, the three of us that were sailing Jolie Brise bare to the buff, a blazing sun and a great cloud of red canvas, the masthead spinnaker emptying itself into the balloon jib, the mainsail and topsail broad off and all drawing, a steady eight knots reeling off on the log and nothing visible ahead, for the canvas hides everything."

In 1938, as war threatened in Europe, Mortimer decided to stay in America. Jolie Brise was put up for sale and Cumberlege was out of a job. Later that year Nancy became pregnant (Marcus was born at the end of 1938). What transpired during the next two summers is unclear but Mike's hectic sailing schedule continued. In November he responded to a letter from Pangbourne with one of his own. It contains more than a clue to his lifestyle as he describes voyages in a yacht called Landfall owned by another American millionaire.

"Your letter has been half round Europe with me, from the Greek islands to the Baltic and through the (Munich) crisis in Germany, escaped by the skin of its teeth, was lost for a while in Holland and still stuck to me, intending to be answered on a single-handed voyage from Malta in a three-and-a-half tonner -I had to leave Landfall in Germany and shall be going to bring her south in the early Spring (of 1939) for a cruise in the Greek islands, which part of the world is my happy hunting ground."

Another friend of Cumberlege's father was Admiral J.H.G. Godfrey. In 1939 he became the livewire Director of Naval Intelligence and was, to quote Platon Alexiades, "always supportive of Mike and closely followed his career." It was Godfrey who had the idea of using civilian yachtsmen like Cumberlege to reconnoitre Italian and Greek coastal defences. During two long voyages around the Adriatic and Aegean in the spring and summer of 1939, again accompanied by Kotrba, Mike scouted many locations that were to become even more familiar to him in the years just ahead.

At the start of 1940 Cumberlege was called up for war service. For the first six months of that year he was attached to a French anti-smuggling unit based in Marseilles. After France capitulated, he had a short spell as a liaison officer to General de Gaulle before spending time in the Cape Verde islands, possibly helping to prepare for a British takeover that never happened. Late in January, 1941 he was transferred to SOE's Middle East section. Soon after Admiral Godfrey moved him to HMS President, the cover given to naval officers seconded to undercover work. In mid-February a telegram confirmed that he had been appointed to lead para-naval SOE operations in the Middle East based in Haifa and Alexandria.

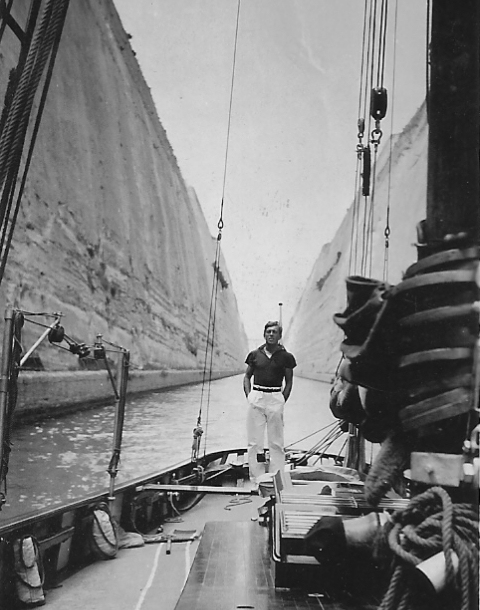

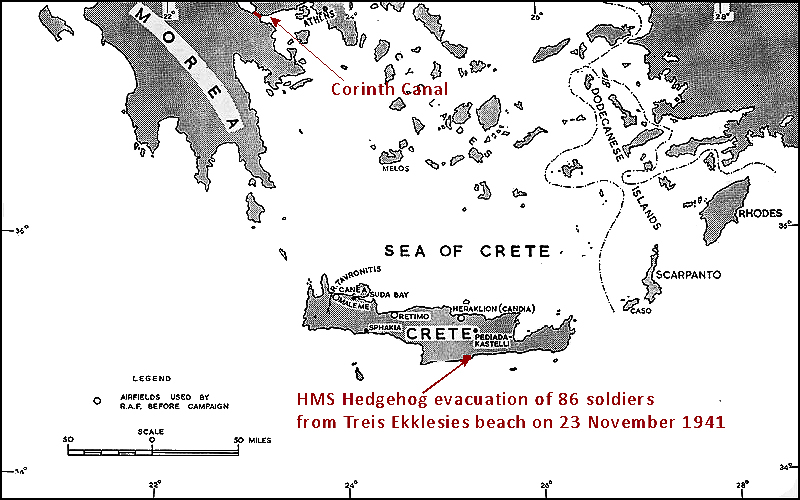

Undeterred, he set about making his presence felt. Within weeks of arriving in the Middle East and taking charge of the trawler, a lightly armed caique called HMS Dolphin, he piloted the vessel and its crew (who included his cousin Cle) through the Corinth Canal, leaving behind a time-delayed mine and depth charges. The objective was to block the strategically-important, narrow waterway to slow the German advance south, but the charges failed to detonate.

The failure of the April, 1941, attempt to block the Corinth Canal led to recriminations all round. The mission was overseen by the Naval Attache in Athens, Rear Admiral Charles Thurle, who disagreed with the policy of blocking the canal and failed to make adequate arrangements "for a task already rendered difficult by earlier lack of planning on his part" in the words of the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral J.H. Godfrey. To be fair to Thurle, he was also trying to arrange the despatch of the Greek Navy to Alexandria and the evacuation of shipping from Greece so may have had more pressing matters on his mind. In any event Thurle provided a short account of the mission when he reached Alexandria in June.

The following month (8th July) Cumberlege wrote up his report of the mission. In this he stated that his team, which included his cousin Major Cle Cumberlege, had laid one magnetic mine and eight depth charges in the canal as agreed with Admiral Thurle on April 23rd. Both had seven-day delay fuses. The team then returned to Athens on Dolphin without having aroused any suspicion "but receiving a hostile reception from the natives we decided to make for Nauplia (Crete) with the idea of assisting in any way possible." In Crete he heard from a Greek business man that the canal had been destroyed" but this proved to be incorrect. The likeliest explanation seems to be that the charges and mine went off but were insufficiently powerful to have caused any significant damage to the sloping banks of the canal at the point where they were dropped.

The Director of Naval Intelligence in his report of the affair in mid-August went out of his way to exonerate Cumberlege from blame. "Lt. Cumberlege RNR, who is reported as having carried out his work 'boldly and efficiently within the terms of his instructions' is an officer exceptionally well qualified for work of this nature. He was attached to the Special Operations Executive and later to the Naval Attache in Athens owing to his unrivalled knowledge of the Aegean, his seamanlike qualities especially in small sailing ships, and his natural aptitude for just such tasks as the one which is here reported upon."

Soon after attempt to block the Corinth Canal Dolphin was in action against attacking German aircraft in Piraeus, claiming two 'kills.' Days later Cumberlege "a bearded naval officer with a gold ring in one ear" in Beevor's words - headed to Heraklion as the Germans attacked Crete. At one-point Dolphin entered Heraklion harbour after a mission up the coast just as the city was falling to the Germans and was fired at from the dockside. Seeing a swastika flag on the power station, the caique turned around and left sharpish.

Over the next few days Dolphin and her crew ducked and weaved for their lives, on one occasion waving in friendly fashion at a patrolling German aircraft. At the entrance to Suda Bay they engaged Stukas with Dolphin's pair of Oerlikon anti-aircraft cannons and a two-pounder gun. Then the caique's troublesome engine failed, forcing Cumberlege back to Canea harbour in northwest Crete where Dolphin was scuttled and a replacement called Athanasios Miaoulis found. Within days this boat was attacked in the Libyan Sea by a Messerschmitt 110 fighter. Cumberlege was wounded and his cousin and another crew member killed. Athanasios Miaoulis limped in to Mersa Matruh to a hero's welcome from the Navy.

Some 5,000 Allied troops were stranded on Crete after the German invasion and the chaotic Allied withdrawal. Cumberlege was in the thick of the action, rescuing as many of these 'stragglers' as possible. In September an SOE memorandum proposed that he be inserted onto Crete with three other officers to assist the evacuation and organise resistance. His qualifications, the memo noted, included 'the knack of understanding and making friends with Cretans (who knew him as 'Skoularikos,' the man with the ear-ring) and sabotage. Later that month Cumberlege wrote a six-page paper fleshing out this proposal.

Events on the ground overtook the suggestion, the coast of Crete was largely sealed off by the Germans and in October and November Cumberlege was fully engaged making repeated, highly dangerous forays in the slow-moving caiques Escampador and Hedgehog to rescue Allied servicemen from remote beaches and convey them to waiting RN and Greek vessels further out to sea. In all about 550 Allied troops were retrieved this way. The official New Zealand history of the Second World War, for example, records how Mike organised two successful rescues of New Zealanders.

Once pre-arranged evacuations became impossible he spent three weeks surreptitiously mapping the deserted south coast of Crete between Cape Litinon and Tsoutsouros Bay looking for landing beaches and hide-outs for small craft and landing a few agents and supplies, without being detected. An SOE assessment made in January 1942 stated, "these operations have so far been very successful." For this work Mike was awarded the DSO and the Greek War Cross.

Cumberlege's extraordinary daring-do record led to a decision early in 1942 to expand SOE's para-naval force. Eventually it totalled 14 boats, based anywhere from Turkey to Cyprus, Egypt and Libya. Part of this unusual force became known as the Levant Fishing Patrol. An inside account of its activities written in mid-1945 estimated that nearly 300 operations were carried out in the eastern Mediterranean from 1941-45, 112 British servicemen were involved and 206 enemy craft captured. "The only casualty was a six-ton caique." The remainder of the winter of 1941-42, though, saw few SOE probes in Crete "owing to the absence of suitable craft" and poor weather. Instead time and effort were put into a 'caique enticement scheme' to induce nervous Greek trawler owners to sell their boats.

In the Spring of 1942 Mike had a bout of typhoid and returned to London in May to be with his wife and son. Officially he was on medical leave. Meanwhile, as Rommel broke through Allied positions in the Libyan Desert, retook Tobruk and threatened Egypt, the importance of the Corinth Canal to German lines of supply was again emphasised. After a couple of months' recuperation, he was asked formally by the Admiralty in July to produce a new plan to block it.

What became known as Operation Locksmith had its origins in lessons learned from the failure of the earlier attempt to block the waterway. Cumberlege realised that limpet mines were too small to cause more than temporary dislocation to canal traffic. With Admiral Godfrey's support he persuaded the RN Mining School in Havant to build a special 45lb high explosive mine which would be detonated by the magnetic field of a large ship.

The raiding party would be given five of these mines and five counter mines to cause simultaneous collateral damage. The crippled vessel, Cumberlege reckoned, would block the canal long enough for the RAF to come in and finish the job. He proposed a party of five Allied commandos that would cooperate with an Athens-based resistance group tasked with providing a caique and Greek-speaking crew that would sail through the canal and plant the mines. The commandos would be inserted into Greece by submarine. Based on Cumberlege's pre-war knowledge, a landing site was chosen at an isolated, treeless spot close to Cape Skyli and not far from Poros in the Peloponnese.

With the advantage of hindsight, there were many flaws to this plan. The mission statement was clear enough - "To block the Corinth Canal, thus forcing ships round Matapan and making them more vulnerable to submarine attack." But the practical details were intricate and overly dependent on outside help. The first flaw showed itself at once when only two of the eight men suggested by Cumberlege to be part of team turned out to be available - a Rhodesian Black Watch sergeant called Jumbo Steele, and Mike's old deck hand Jan Kotrba, at the time based in England in the Czech Army in exile. Cumberlege then selected a wireless operator, the Yorkshireman Tommy Handley, whom he had never met and cut back the party to four, none of whom spoke Greek.

A second flaw emerged at RAF Lyneham on the afternoon of November 18th when Cumberlege, having been told that he could load three tons of carefully selected stores for the flight to Egypt, was forced to leave behind a third of these supplies, including three vital wireless sets, to accommodate some unexpected VIP travellers on the plane.

Seven weeks later on January 8th, 1943 Operation Locksmith began in earnest when Cumberlege and his team, all in uniform, left Beyrouth on a Greek submarine. The landing at a cove near Poros went smoothly and two tons of weapons and supplies, as well as substantial funds, were hidden close to the shore by a deserted house half an hour by boat from three enemy posts. Radio communication was established soon after. A frightened Greek household was approached - "the fear of reprisals is universal;;;our presence was unwelcome for this reason only" wrote Cumberlege in his first progress report - so a rudimentary 'house" was erected in the hills. For the first two weeks the four lived entirely off their own supplies.

Small Greek caique common in the Aegean Sea. Image from the Leopold Mitchell RNVR (South African Division) collection.

At this point a third amber light flickered when the leader of the Greek resistance group in Athens responsible for providing a caique to Cumberlege and his team was shot dead in the street by Italian police. A courier arrived from Athens but spoke no English - a fourth issue. "We have been hampered by not speaking Greek," admitted Cumberlege in a summary report. The bad news was conveyed somehow as was the decision of the owner of the caique supposed to drop the mines to withdraw from the operation. A delay ensued until a second boat and crew were unearthed. "The (go-between) shows keenness and enthusiasm now (but) is also inspired with the Greek spirit of procrastination," observed Mike wryly in his next message.

Eventually the new caique and a three-man crew turned up near Poros. In early March the vessel was loaded with eight mines, arriving at the Sipori Islands near the canal at dusk. Next morning, as Cumberlege was in the water fixing the specialist explosives on to the bottom of the caique prior to its passage through the canal, and Steele was on deck, a German patrol vessel suddenly materialised from nowhere. "The position appeared desperate,"he wrote in Progress Report No. 2, "but hasty steps were taken." By the time the Germans came alongside to conduct a stem-to-stern search the two commandos had been hidden away in a false bulkhead and went undiscovered thanks to 'the calmness and subterfuge of the Greek captain."

The caique was then cleared for passage. At dawn on March 5th Cumberlege and Steele disembarked into a dinghy seven miles from the entrance to the canal. Shortly after an Italian guard came on board. All the counter mines, camouflaged as petrol tins, were dropped unobtrusively from the stern and the specialist mines stuck to the hull of the caique detached. Cumberlege and Steele travelled overland back to their hideout on the Herimone Peninsula and made wireless contact with Cairo on March 11th. Everyone waited for the explosions - in vain.

Ten days later it was concluded by SOE in Cairo that the mission had failed; in all probability the mines were too small and fragile. Cumberlege seemed undeterred and cabled that the actual mining operation had "presented no serious difficulties." His team, he announced, was prepared to remain in the area to make another attempt if improved mines could be constructed and delivered to him.

That was really the last positive news anyone heard from Mike Cumberlege and his colleagues - one of 140 messages sent to Cairo by the party. On March 19th he reported that Italian secret police were searching for his party, the local inhabitants had become 'hostile' and the mission's position was 'difficult.' Early in April a small German patrol stumbled on Cumberlege and Handley.

Cumberlege opened fire and the patrol "withdrew in disorder." But the mission's hideout had been discovered and had to be abandoned in a hurry. A retreat into the mountains followed. In the haste secret radio codes and a wireless transmitter were left behind and later retrieved by the enemy.

It was the beginning of the end for Operation Locksmith. In the days that followed larger enemy patrols scoured the Poros area. Cumberlege and Steele returned to the hideout to collect stores and funds only to discover that 2,000 sovereigns had disappeared. Three days later, on its one remaining transmitter, the group received a message ostensibly from SOE Cairo that a submarine was coming to rescue it. On the night of April 30th, with some hesitation, the mission members boarded a rowing boat and moved towards a flashing light they could see from the shore. It was a trap. Mike Cumberlege, Jumbo Steele, Jan Kotrba and Tommy Handley were captured and taken away. In an attempt to exploit their coup, the Germans then twice tried to lure a British submarine to Poros to evacuate the party with false wireless messages using the captured codes.

After the war efforts were made by SOE to discover what had gone wrong. The most exhaustive, by the Balkan Counter Intelligence Service, visited Poros and spent a couple of weeks there interviewing locals. It concluded that the Locksmith party had been betrayed either for money - the cache of gold, diamonds and cash that various locals had learned was in Cumberlege's possession - or by pro-German sympathisers on the island. Suspects, including several who had splashed out in ostentatious ways in the 1943-45 period, were arrested as the Greek civil war began in 1946, but never tried.

At the start of May, 1943 Cumberlege and his colleagues were taken to Averoff prison in Athens where daily executions of Greek resistance fighters were conducted by Italian fascist guards wielding wire whips. Five months earlier Hitler had given his infamous order that captured Allied commandos, in uniform or not, were to be summarily executed. For whatever reason, this was ignored at Averoff. Instead Cumberlege was tortured before being moved to Mauthausen camp near Linz in Austria.

Set up to house "Incorrigible Political Enemies of the Reich," Mauthausen was not so much a concentration camp as extermination centre averaging 500 executions a day. Here Cumberlege's torturer, according to a message he smuggled to London in February 1945, was one H.I. Seidl of the Gestapo. Seidl was executed for war crimes in 1947. Under duress Cumberlege signed a statement agreeing that the Locksmith party were saboteurs despite being captured in uniform and in contravention of all the norms of war.

In January 1944, on the personal order of Ernst Kaltenbrunner (then chief of the German security services; he was tried at Nuremburg and executed), the four men were transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp 30 kms north of Berlin. Here they were placed in solitary confinement in the T-shaped Zellenbau (cell block) - a complex of 80 cells for notorious (in Nazi eyes) "violators of international law." For the remainder of their lives Cumberlege and his companions survived in dank cells 2.5 metres by 2 metres and were treated as common criminals, dressed in blue and white striped convict clothes, fed wurzels (a type of beet root) and not allowed Red Cross parcels. Each morning they exercised separately for 15 minutes in an open-air yard.

Sachsenhausen also held large numbers of Russian, Polish, Jewish, Dutch, Norwegian and Danish prisoners as well as a few British and American airmen and commandos. Conditions throughout the camp - a training school for all concentration camp personnel - were appalling and mass killings in a gas chamber or by hanging or shooting routine. Right outside the camp was the central command for all Nazi concentration camps, headed at the end of the war by the former commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Hoess.

At his war crimes trial by the Soviets in 1946 the last Sachsenhausen commandant, Anton Kaindl, blandly admitted that 'more than 42,000 prisoners were exterminated under my command (1943-45), including 18,000 in the camp itself." Kaindl, it turned out, visited the Zellenbau twice a week to inspect conditions.

Much that is known about Mike Cumberlege's final days comes from other inmates in the Zellenbau who survived the war. One such, an RAF officer called H.M.A. ('Wings') Day who was held in a cell opposite, managed to communicate with Cumberlege and learned the details of his capture and 'severe interrogation'in Mauthausen. Another, the flamboyant commando Jack Churchill, smuggled out two encrypted messages from Cumberlege when he was repatriated in April 1945. In one of them, sent to his wife Nancy in late January, 1945 and his last message, he begins: "I think I have forgotten how to write but will try it for it is really almost the one opportunity of direct contact I will get. Well sweetheart it has been perfectly bloody, no chance to write and always wondering if you are perfectly happy with Master Marcus and Bira (the cat). I must admit I had expected to be able to have heard of you in some way but it really seems there is no hope and I have quit trying to kick against fate. You will be happy darling to hear something of me and please do not worry. I am absolutely fine, a bit thin damn it and never have quite enough to eat. I had not expected anything else anyway."

Cell 77 next to Cumberlege (Mike was probably in cell 75) was occupied by a Ukrainian resistance leader called Tara Bulba-Borovets. In 1981, the year he died, the Ukrainian diaspora in Canada published his autobiography Army Without a State, written in Ukrainian largely from memory. Thanks to a resourceful researcher in Kiev, the text of this book with its references to Mike was unearthed in 2016, so adding more detail about his existence in the camp.

Bulba-Borovets and a dozen or so of his compatriots had been imprisoned in Sachsenhausen at the start of December, 1943 while the Germans attempted to persuade them to fight against the Soviets in a specially-formed brigade on the Eastern Front. Coincidentally, the Allies had begun a mass air campaign against Berlin the month before their arrival which was sustained through most of 1944/45. As Cumberlege and his three companions reached the camp in January, 1944 the raids had become a daily occurrence. Sachsenhausen was not hit directly, except by incendiary bombs which caused a lot of fires, but nearby were some industrial plants run by the camp. Bulba-Borovets recalled:

“We passed endless days. The sleepless nights were even longer. The Zellenbau swayed, like a ship on waves, but remained intact. While SS troops hid in a bunker, the prisoners sat in cages…The roar of engines, bombings, gunfire, the howling sirens, the cries and laments of the slain and wounded mingled in such a terrible cacophony that it was harmful to damaged people even those with the strongest nerves.”

The Zellenbau, writes Bulba-Borovests, had about 90 cells located on either side of three corridors built in the shape of a letter “T”. “The whole of Europe” was represented in the block including Poles, French, British, Romanians, Bulgarians, Serbs and Croats. The Ukrainians, whom the Nazis hoped to turn into allies, and others were permitted a one-hour walk most days. This allowed them to set up a rudimentary communication system. “There is nothing worse for the lone prisoner than isolation. All prison inmates fight this curse. Yet even with a strict regime of isolation prisoners always find ways for friendly contact.”

Bulba-Borovets goes on to describe the day-to-day atmosphere in the Zellenbau block: “The ‘machine’ carried out shootings all the time. We all await our turn at any moment. Life is concentrated on one point – in the ears. All the horrors of the bombing every day are like a psychological paradise compared to the endless sleepless nights. When a sunrise occurred, it brought some joyful hope that finally, perhaps, the bombing torment might deliver some hope and bring an end to this torture. But the desired end did not come. Long summer days (in 1944) flew by like lightning but the short nights seemed an eternity. The quietest mouse rustling in the corridor sounded to us like a step taken by an SS boot. And when a guard did reach our corridor, for us all it was an eternity as we guessed which cell. Was it for us or not for us?”

Escape plans were hatched, then discarded – “Once a plan, again some new hope for a few days. Then complete hopelessness. Sachsenhausen is a city with dozens of walls covered with electrified barbed wire, tower guards with machine guns, searchlights and patrols with hundreds of dog.” This might be followed by apathy – “the severest of threats to a prisoner.”

Communication among the Zellenbau prisoners was possible in a variety of ways although speaking to other prisoners was prohibited. One favoured method was to write in the margins and spaces of German propaganda newspapers handed out to the prisoners each day by their gaolers, particularly the Volkischer Beobachter published by the Nazi party. Sometimes small scraps of this paper with bits of news were thrown into a cell by those taking exercise near a cell window or concealed in the buckets used for toilet needs that were taken out by orderlies. Another method involved tapping on the thick, inter-connecting cell walls in Morse code or using Morse code by tapping messages on the palms of one’s hand during exercise periods for other prisoners watching from their cells.

From somewhere in the camp the Ukrainians acquired a supply of tobacco. This was turned into Vinnytsia shag (named after a tobacco factory in Ukraine) and rolled into large, rough “cigars.” “We passed them through the ‘mail’ to our British comrades together with scraps of news. I was the contact of a sailor called Michael Cumberlege, the son of a retired Admiral. Morse signs thanked us for the information from the press and the ‘Havana cigars.’ Michael joked every time that once we got out of here we would immediately smoke two large, genuine Havanas…He was an extremely good companion in distress. Always cheerful, occupied with new ideas, very friendly, inventive, honest, modest, steady and resistant to all prison torments and surprises.”

At the end of October, 1944 Bulba-Borovets was let out of the Zellenbau and told by the Nazis that he would be released from the camp on certain conditions, in particular that the Ukrainians would agree to “mount a common front against communism.” Negotiations dragged on until early-March, 1945 when the German government issued a permit for the organization of a Ukrainian army. Bulba-Borovets’ detachment surrendered to the western Allies in May, 1945 and he was interned in Italy. He emigrated to Canada in 1948.

Mike Cumberlege and Jumbo Steele (in Cell 5) remained in Bulba-Borovets’ memory more than 30 years later. “Of all our English friends in the Zellenbau, only one escaped (possibly a reference to ‘Wings’ Day of the RAF, but he names ‘Falconer’ or ‘Faulkner’). The fate of the rest is unknown. There is speculation that at the end of the war they were shot. No one knows. Maybe some of them are (still) alive. Every war has millions of different surprises. Thousands of people have been found alive since the war, many older than his (Mike’s) age. So God may have protected our unforgettable friend Michael and his other comrades in trouble. All katsetnyky (Ukrainian slang for concentration camp prisoners) will forever be a separate large family of fraternal friendship – living witnesses to the nightmare of totalitarianism.

The fullest and probably most accurate account of Cumberlege's final days was given to the formidable SOE intelligence officer Vera Atkins who managed its French section for much of the war. Determined to discover the fate of missing SOE agents, she had joined the War Crimes Investigative Section of the Judge Advocate's department and journeyed to Berlin in 1946. Here she met three times with Paul Schroter, a German prisoner at Sachsenhausen.

Arrested in 1936 as a member of the outlawed Bible Society, Schroter had ended up as an orderly in the Zellenbau. On about April 10th, 1945, he said, he saw the four members of the Locksmith party taken out of their cells and transported by ambulance to the camp execution area. "I was not an eye witness to the execution but knew only too well from the usual procedure preceding and following such executions that they were done to death," Schroter stated.

Most likely the four were subjected to an elaborate charade, taken to a three-room complex, told to undress and examined by SS 'doctors' and made to stand on a weighing /height-measuring machine facing a wall opposite. At this point a sliding hatch opened in the wall behind the prisoner who was then shot in the neck - a method of killing apparently perfected for disaffected Wehrmacht officers in 1941. Music was played to disguise the noise of the shots. Afterwards the bodies were taken to the crematorium and orderlies like Schroter ordered to collect personal belongings from the victim's cell and take them to the camp boiler room to be burned.

Other post-war testimony, particularly from a Norwegian called Leif Jensen who was in Sachsenhausen, suggests that Schroter, who admitted to a poor memory for dates, may have got his months mixed up. Still, Schroter had no obvious motive to lie unlike the Zellenbau guard commander, Kurt Eccarius, whose self-serving testimony to the Soviets included a claim that he last saw Cumberlege in February 1945 when the four men were sent to Gestapo HQ in Berlin. One way and another an execution date in the first half of March is likelier.

Why they were murdered is clearer. In a declaration made to a British interrogator, Rudolf Hoess asserted that at the end of January or early February 1945 he received an order from the head of the Gestapo that all concentration camps were to be evacuated as Soviet armies closed in on Berlin. Each camp commandant was ordered to compile a list of internees who 'might prove dangerous' - that is, Allied agents and commandos who had been maltreated. They were to be executed before the camp was cleared. Kaindl supplied such a list and informed an SS general that the order had been carried out. The evacuation of Sachsenhausen's 47,000 surviving inmates began on April 21st, 1945. The next day, when the Soviets arrived, no more than 4,000 were still there.

For many months after the war efforts were made by the Naval Intelligence Department in the Admiralty, and by Nancy Cumberlege and her redoubtable father-in-law Admiral Claude Cumberlege, to discover the fate of Mike Cumberlege and the Locksmith party. None were conclusive. Early in December, 1946, Cumberlege was awarded a bar to his DSO "for great gallantry and determination of the highest order in clandestine operations behind enemy lines in Greece in January and February, 1943." The following month the Admiralty informed the family for the first time about Mike's wartime career. He was 39 when he died and had packed a tremendous amount of intense experience into his short life.

As Platon Alexiades concludes in his book Target: Corinth Canal 1940-44, "Fortune did not smile" on the four brave men who embarked on Operation Locksmith. "But they had volunteered for a mission and (they) never faltered." Perhaps, though, the last word should go to the 'correspondent who knew Cumberlege intimately' and penned a tribute to him in Issue 76 of The Log of the Nautical College, Pangbourne, which first set off my search. It reads:

[Copyright Robin Knight and family 2013. The moral right of Robin Knight to be identified as the author of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of Robin Knight]

© 1999-2025 The Royal Navy Research Archive All Rights Reserved Terms of use Powered byW3.CSS

Comments (12)

My Grandfather was a member of the group that got off crete in May of 42 in the Saunders/Cumberledge group. Marked as F Jerome ( Francisco Jeronimo, Layforce). He went back to the commandos and end ended up in 2 SAS. Settled in Cardiff after the war.

With the assistance of Platon Alexiades (in Montreal), and an awful Google translation, Robin and Andy have been able to piece together more facts about life in Sachsenhausen as Cumberlege experienced it.

Excellent job to preserve UK navy heroes' history. Though I've got no connection to it (I'm Ukrainian) I read your articles with great pleasure. And there is still a connection of Mike Cumberlege to Ukraine... He was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen camp together with Ukrainian liberation movement hero Bulba-Borovets, leader of Polisska Sich. They were in neighbouring solitary prison cells in "Zellenbau" block, and knew each other well. Bulba-Borovets has great recollections of Mike and if you're interested in it - just feel free to use my mail and I'll share details of it. Kind regards,

Andy