X

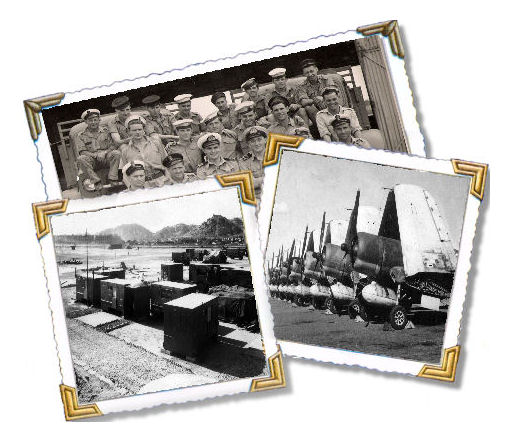

The reminiscences of Leading Air Fitter (Engines) Reg Veale.

Reg served with M.S.R. 6 and wrote down his memories in the form of a

story ‘A WISH COME TRUE’ which he has kindly allowed to be reproduced here.

Copies of his work are lodged with the Fleet Air Arm Museum, and the

University of Leeds.

Early days

Back in the early 1930's going to the cinema was a regular Saturday morning occasion, I don't think that my friend and I ever missed a matinee at the DELUXE theatre in Gloucester where, with great excitement, we used to watch serials such as The Last Of The Mohicans, The Lone Ranger, and Buck Rodgers etc. During the interval, the organ would rise up from the pit and we would sing along, with the help of words pointed out on the screen by a bouncing ball. It was after this that we'd be shown a travelogue and I well remember the paradise islands of the Pacific they portrayed: palm trees swaying-gently in the breeze, beautiful blue lagoons and exotic food in abundance.

Visitors to those shores were embraced by dusky maidens in grass skirts, festooned with garlands of flowers and regaled by the cascading harmonies of Hawaiian guitars to which the grass skirted ladies sensually gyrated. Trance like, the closing words of the narrator never varied: "And as the golden sun sinks slowly in the west, we say farewell to this island of paradise". I used to long to visit such an island and dream about my wish coming true.

Joining M.S.R. 6

On the 9th of December 1944, having been seconded to the Royal Air Force for nine months, I received a draft to return to H.M.S. Gosling in Warrington. This Fleet Air Arm camp was where I had received my basic training in March 1943 and I associated it with square bashing and disciplinary training that I and other raw recruits had been put through.

What was the reason for my return? During the customary F.F.I, and general joining routine, I met a few other bods who were wondering the same thing. All was revealed in a pep talk on how we were going to win the war and how we were to be trained in the art of self-defence, jungle fighting and survival. On the matter of survival, the only thing I knew was that you should never eat yellow snow.

Three months of intensive Commando training followed, in the middle of winter - how we ever survived the ordeal, I’ll never know. I was supposed to be a Leading Air Fitter and so what the hell was I doing, fighting fit and dressed in Khaki battle dress? At last! Order of the day: 14 days leave, and then report back to Gosling. 7th of March 1945: marching orders, destination Liverpool Docks. As part of a unit known as M.S.R.6, we piled into the usual mode of transport, the faithful old Bedfords.

Off to Australia

Later while embarking on the cruise liner Empress of Scotland, close observation revealed that the word "Japan" had been blacked out and "Scotland" painted over it. Was this an omen?

With 10,000 souls on board, we joined a convoy, and headed north round the tip of Ireland and then south into the Atlantic before parting company with it at the Azores; the convoy continued onwards to the Med. Swinging to starboard, our course was south west across the Atlantic. With our speed increased from 6 to 22 knots it would be almost impossible for a submarine to sink us (so we were told). The old Empress shuddered as the taps were opened up, but she finally settled down as she reached cruising speed en route for the Panama Canal.

Early on in the journey, I found night times the worst. I clearly remember the day the Skipper assembled us on the promenade deck and told us that we were heading for Sydney, Australia, to join the Pacific fleet. We were given a lecture on how to survive should we have the misfortune of being torpedoed. That night in my bunk I was looking at a porthole immediately above my head and like all others it had been covered over with a thick steel plate. I realised that we must have been very close to the water line and that if attacked, a torpedo would enter the ship just below my bunk and that the Skipper's lecture seemed a complete waste of time; in any case I couldn't swim and even if I could, where would I swim to? After weighing up the situation I remembered that someone once told me that drowning was quite a pleasant experience, from then on for some reason or other, all doubts in my mind disappeared. On reflection, how can anyone know that drowning is a pleasant experience; I sometimes think that somewhere along the line we were all brainwashed to think that it would never happen to us.

After a few days out we ran into rough weather; it appears that the Captain had taken evasive action to avoid the worst part of the storm but even then, gale force winds lashed the old Empress and you could hear the creeks and groans as she battled against the elements, there were moments when I thought that all my birthdays had come at once; this was my first- introduction to rough weather and sea sickness.

As the days passed, life became very boring; nothing to do but pace the deck or stand and watch the hypnotic effect of the bow wave making instant changing patterns, or stand aft watching the wake left behind like a wide watery street reaching back to infinity. We were by now entering the tropics: The Empress was beginning to warm up; conditions below decks were gradually becoming almost unbearable. The holds were opened and large canvas sheets hung in an attempt to channel fresh air to the lower decks. Order of the day: sun bathing. Having received a lecture on the dangers of over exposure, on the first day we were only allowed 10 minutes on the front and 10 minutes on the back. This was extended at the rate of 5 minutes 'a day until we all had an acceptable tan protecting us from serious sunburn. Some of the lads did not heed the initial warning and suffered great agony of large blisters on their shoulders that could only be described as having the appearance of fried eggs. Because the injuries were self-inflicted, they received very little sympathy from the sick bay and had to suffer in silence.

At long last, land ahead! We had reached the port of Colon, the entrance to the Panama Canal. The Canal Zone had been occupied by the American army to ensure the safety of Allied shipping. We were allowed ashore, but only in the immediate vicinity of the Empress. Something I shall never forget is when a native attempted to sell bananas from the dockside. They were arranged on, what looked like, two massive hands each being almost as big as himself and suspended from a pole across his shoulders. Not having seen a banana since the outbreak of war, it was like showing a red rag to a bull; the poor fellow was mobbed. The unfortunate native disappeared without trace.

While the Empress was refuelling and taking on supplies the American U.S.0. (the equivalent to our E.N.S.A.) entertained us with the big band of Tommy Dorsey and the ever-popular Dinah Shaw.

We also enjoyed a demonstration by the American Jitterbug champion and, if my memory serves me right, Paddy Lewis the youngest member of M.S.R. 6 was one of the volunteers to have a go. Coca Cola and doughnuts were the order of the day, then back on board and the fantastic experience of passing through the Panama Canal. With just inches to spare we climbed up through the locks to the freshwater lake; what a relief! freshwater showers, the first since leaving home. Leaving the lake behind, we continued onwards and down to the Pacific (which I'm told, is higher than the Atlantic). We had witnessed the result of a feat of engineering beyond all words to describe; it has to be seen to be believed.

After a few days the Empress, continuing South West, began to cool down, making conditions more acceptable for the last stretch of our journey. Eventually we reached our destination, and what a welcome sight as we passed through Sydney Harbour Heads was the old coat hanger bridge spanning the harbour and the view of the city beyond. All around us, anchored in the harbour and tied up to quays were ships of every type Imaginable.

We were told that they were part of the famous Fleet Train on which we were later to rely on for our existence. Without them, indeed, the B.P.F would never have existed. On disembarking, and after a short journey out of Sydney, we arrived at R.N.A.S. Bankstown, or H.M.S. Nabberley, manned by M.O.N.A.B. 2, where we were soon involved in building Seafires which were transported to the Fleet by means of the escort carriers of the Fleet Train.

&In the first week in May we were given 14 days leave. My good pal, Harry Watts and I opted for a stay at a sheep station at a place by the name of Gidley. The station was in excess of 400 square miles, we were warned not to wander off out of sight of the homestead on our own; it was all too easy for anyone not conversant with the bush to get lost with serious consequences. On the 8th of May we received the news that Germany had surrendered. Mr Robinson the station manager immediately organised a Victory parade and Thanksgiving service at the Gidley war memorial. My claim to fame is that Harry Watts and I, were the first ever and only, F.A.A. ratings to lead a Victory Parade.

On the move again

After sampling the generous hospitality of the Australian people, we embarked on the escort carrier H.M.S. Arbiter on the 18th of May to join up with M.O.N.A.B. 4 on the island of Ponam.

At last my wish of my younger days was about to come true; I was on my way to see for myself the swaying palms and dusky maidens of a paradise island in the South Pacific, but things were not quite as they had been portrayed in the travelogues. Firstly, I found out that the Pacific Ocean was not as tranquil and blue as they had made out. After about four days out somewhere around New Guinea, we hit a typhoon.

Huge waves broke over the flight deck which was loaded with supplies and, despite being securely lashed down, several crates were washed overboard.

During the height of the storm the Arbiter registered a list of 48 degrees and, without doubt, if it had not been for the full tanks of aviation fuel acting as ballast, she would have turned turtle. Had the tanks been only half full, the weight of fuel shifting to one side would have assisted in taking her under, fortunately the Captain had been well briefed on taking evasive action when confronted with such severe conditions.

There was an event on the 18th of December 1944 that involved the U.S. Navy's Pacific Fleet and was little known to the R.N. or to the public. The Scene for the catastrophe was set about 300 miles east of Luzon. During support missions for the invasion of the Philippines, the fleet was caught in the middle of a vicious typhoon. Three destroyers, the Hull, the Monaghan and the Spence quickly capsized and went down with all hands. Carriers Miami, Monterey, Cowpens, San Jacino, Cape Esperence and Altamaha were all seriously damaged, as were D.D.Aylwin, Dewey and Hickox, lesser damage was incurred by 19 other ships. Serious fires broke out on three carriers when aircraft smashed into each other in the hanger decks; 146 aircraft on various ships were lost overboard or sufficiently wrecked by fire or impact to warrant their scrapping. 790 men were killed and 80 were injured. Rolling of 70 degrees or more was reported from destroyers that survived. The severity of the disaster was due to the Fleet Commanders trying to maintain Fleet courses, speed and formations during the storm. Commanders failed to realise that they should have given up such attempts and instead, directed all attention to saving their ships. After this terrible tragedy, Admiral Nimitz issued orders to the effect that the safety of the ship at all times was of paramount importance even if it meant dropping out of battle formation; the ship would be saved to fight again and, in any case, the enemy would be similarly affected by turbulent conditions.

On entering the Bismarck Sea, we were warned that we'd come within range of enemy aircraft based at Rabaul in New Britain. The damage control party was closed up and all bulkhead doors kept shut, this being normal routine when in an operational area. A Corsair, which had been lashed down on the catapult, was checked over; it had not suffered any damage during the storm. An interesting thought: had it been necessary to have launched the Corsair there was no way that it could have landed back on board with the flight deck loaded with cargo, I presume that the Admiralty considered Pilots and Corsairs to be disposable objects.

Approximately 300 miles further on and we were approaching Manus, the main Pacific Fleet anchorage in the Admiralty Islands. We were lulled by a calm sea, a gentle breeze, the clear sky reflecting on the water, flying fish and dolphins riding the bow wave. My wish had started to come true; all I needed now was the tropical island and a blue lagoon. I was rudely awakened from my meditative state by a blast from the Tannoy, "M.S.R. 6 MUSTER IN THE HANGER DECK" we were told that we would be reaching our destination, Ponam Island, the next day The following morning we sailed into a massive anchorage of shipping, with the similar variety of ships seen in Sydney.

There were tramp steamers, tankers, cargo vessels and rust buckets of all shapes and sizes and nationalities. It was an International Fleet with Officers and men from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, and Canada etc. This was Task Force 112 better known as The Fleet Train. Its anchorage at Manus in the Admiralty Islands was the main forward supply base for the British Pacific Fleet

A wish come true...Ponam Island

After unloading supplies and aircraft the Arbiter weighed anchor and preceded to Ponam Island just three hours sailing from the anchorage, I had at last arrived at my island paradise. Going ashore however was a great disappointment. Where were all the dusky maidens with there garlands of flowers?

Why, in the travelogues, was there no mention of the sun reflecting off the coral and burning your legs, or the sand flies, coral snakes, land crabs, mosquitoes, the high humidity, no flush toilets, no fresh water, tinned and dehydrated food, the list goes on and on. Needless to say no mention was made of the necessity of being armed with a Sten gun.

There was no doubt about it. All those travelogues that I had seen were part of a big con. I felt like complaining but unfortunately there wasn't a complaints department on the island. One Submarine Captain described the Admiralty Islands as the 'Islands of Lost Souls'.

Having grown a full set, and having suffered the agony of bugs getting trapped in it, I decided one morning after a restless night that enough was enough. I set to work with scissors and razor. I clearly remember the white mask that appeared all over my face. My beard had protected my face from the sun and I looked like the Phantom of the Opera, Even so, what a relief! However, my relief had a price attached: I was put on a charge for altering my identity. My pay book had a photo of someone with a beard but the person holding the pay book had no beard. This was a very serious charge and had I been anywhere else I would probably have been hung drawn and quartered or at the very least, been stripped of my hook. Fortunately, the skipper, apart from being sympathetic had a sense of humour. I was given 14 days confined to barracks; it was not recorded on my documents.

On the island we worked from dawn to dusk, there was no time for tropical routine, but it was not all doom and gloom. At times we received the privilege of extended "make and mends" when we would put on boots and gaiters to explore the shallow expanse of the lagoon where every type of coral and tropical fish existed. There was a deep pool in the lagoon, which had been scooped out of the coral with explosives either by the Japanese or the Americans and used for swimming, The water temperature rarely fell below 90F, and the only way to cool down was to stand wet in a slight breeze. As regular as clockwork, we would get an advanced warning of a tropical rain storm, because it was always preceded by the rustling of the palm trees as the wind sprang up.

M.S.R. 6 (Mobile Storage Reserve) was one of the many units making up M.O.N.A.B. 4. Some of us were detailed to the eastern end of the island to operate the dispersal site where, during our time on Ponam, literally hundreds of all different types of aircraft were despatched to carriers of the B.P.F. Due to the unpredictable weather and extreme conditions in the tropics the average life of a British aircraft was 15 flying hours, and of an American aircraft 25 hours. The difference between them was that a Seafire was designed as a short-range interceptor for use in temperate climates, whereas a Corsair was designed for long range and operation under tropical conditions; it even had an air-conditioned cockpit.

Earlier on I mentioned that we had no flush toilets. A walkway approximately 60ft long led to a platform over the sea covered with a roof of palm leaves. Inside was a low bench with a series of holes where one would drop shorts, sit on a hole and contemplate. The most unusual thing about this bench was that at times every other hole would be left vacant to allow each occupier to gaze down the adjacent one while holding in one hand, a fishing line. For some reason there was always an abundance of fish in this area; I have no idea what type of fish they were but we called them s**t fish.

In exchange for a tot of rum, I had obtained from one of the Yankee Sea Bees a primus stove, on top of which a piece of steel plate made a perfect barbecue. After de-scaling the fish it would be placed whole on the plate and well cooked, allowing the flesh to fall off the bones. This left the bones and intestines intact thereby stopping the contents o-f the stomach contaminating the flesh. This fresh meat made a welcome change to our diet.

Wednesday August 15th, we received the good news that the Japanese had surrendered. Order of the day: 'Splice the Mainbrace'. We were warned not to be too complacent; 1,000s of Japanese would not accept defeat and we were still considered to be operational, in fact it was not until March 2nd 1946 that the Americans considered that all hostilities had ceased. Anyone who served in the American forces up to that date were awarded the Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal which was accompanied by the award of a pension for services rendered.

During our stay on Ponam we came under the command of William. F. Halsey who was the Commander of the American 3rd fleet. He was put in charge of all Naval Forces in the South Pacific. At the end of the war the Asiatic Pacific Campaign medal and pension was offered to all who had served under the command of the American Flee. unfortunately for us, the new British Labour Government of 1945 would not allow us this privilege.

There is just one thing, which rather irks me; it is an entry in Ron Lewin's unofficial diary, which makes me very envious of him and everyone who were on board H.M.S. Unicorn. It states; Thursday August 16th 1945 the 2nd day of celebrating has for us proved noteworthy in only one respect, namely the enjoyable dinner provided. The soup was quite commonplace, but the main course of turkey, stuffing, potatoes and green peas was liberal (a whole turkey between nine of us), well cooked and a complete change from the usual monotony of meat. There followed Christmas pudding and finally a raw apple. The ship "piped down" during the morning. Where the hell did they get such an abundance of good food? I think that the best we had was a tin of Spam and dehydrated potatoes. Somebody somewhere owes us a Christmas dinner!

With reference to the end of the Pacific War; sadly and in some ways prophetically, Admiral Rawlings wrote, "I have not seen the personal signals, or indeed seen all the official signals, but I am in no two minds about one thing; that the "fading out" of the task force and the manner in which this is being done is not only tragic, but is one which I would give much to avoid. To me, what is happening to its personnel and its ships seems to ignore their feelings, there sentiments and there pride; in so doing quite a lot is being cast away, for the Fleet accomplished something which matters immensely".

I am not speaking of such enemy they met, nor of the difficulties they overcome, nor of the long periods at sea; I am speaking of that which was from the start our overriding and heaviest responsibility, the fact that we were in a position which was in most ways unique and was in any case decisive; for we could have lowered the good name of the British Navy in American eyes for ever. I am not certain that those at home have any idea of what these long operational periods mean, nor of the strain put on those in the ships, so many of whom, both officers and men, are mere children, for instance Leading Seamen of 19 and Petty Officers of 21.

When I look back on that which this untrained youth has managed to accomplish and to stick out, then I have no fear for the future of the Navy, provided, but only provided, that we handle them with vision and understanding, and that we recognise them for what they were and are-people of great courage who would follow one anywhere, and whose keynote was that the word "impossible" did not exist. And so, I question the wisdom of dispersing a Fleet in the way in which it is now being done. At the very least there should have been taken home to England a token force somewhat similar to that which was left in the operating area with the American Fleet when the tanker shortage required the withdrawal of the greater part of the Task Force. It seems to me that here was a matter, which could have been utilised in a dignified- and far reaching manner-the arrival in home waters of ships who had represented the Empire alongside their American Allies, and who were present, adding there not ineffective blow, at the annihilation of the Japanese Navy and the defeat of Japan.

It may well be that the days will come when the Navy will find it hard to get the money it needs. Perhaps then a remembrance of the return and the work of the British Pacific Fleet might have helped to provide a stimulus and an encouragement to wean the public from counter attractions and those more alluringly staged. The arrival home of a token force at the time of the Victory celebrations might have fixed the British Pacific Fleet more firmly in the public's memory. But it was not to be. In time the Fleet quietly faded away, with the result that the Far Eastern fleets may have been the largest assemblies of Commonwealth ships in history but, like the three old ladies locked in the lavatory, nobody

knew they were there.

In 1995 Harry Bannister of the Ponam Association applied to the Pentagon on behalf of its members for the American Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal in recognition of their service with the American Fleet. As from late 1997,' after 52 years, the American Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal has been made available to all those who served in the British Pacific Fleet

The possibility of pensions or medals, or reflections of a forgotten fleet were not on our minds as we prepared to leave Ponam for home. On the 20th of September 1945, H.M.S. Vindex was anchored off the sea loading line to the south of the island. Fortunately, M.S.R. 6 were to be one of the first units to leave. The Vindex which had set off from Java had on board hundreds of ex-prisoners of war including some women internees. Several of the women were accompanied by young Japanese children and babies. These mothers had offered favours to Japanese officers in the prison camps in exchange for extra rations and medical care for sick and injured men.

The hanger deck was full of stretcher cases of men suffering from the effects of treatment received at the hands of the Japanese. I have never seen such a sight of human suffering in all my life than that which I witnessed on that day. It made me realise h idyllic our lives had been in comparison, and that my youthful wish had actually come true: I had visited the island of my dreams in the South Pacific with its waving palms and blue lagoon. ...And as the golden sun sinks slowly in the west, we say farewell to that exotic paradise island of Ponam

Reg Veale

Comments (0)